Zootopia 2

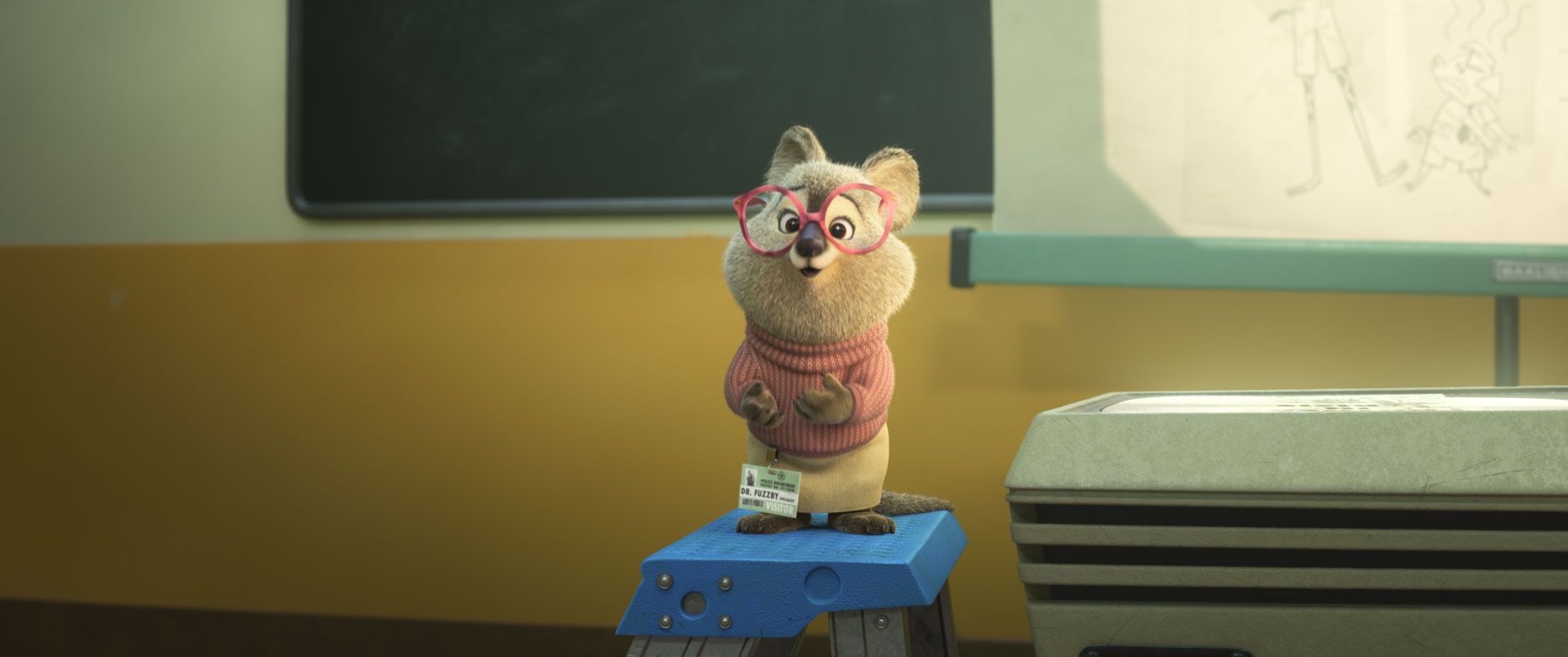

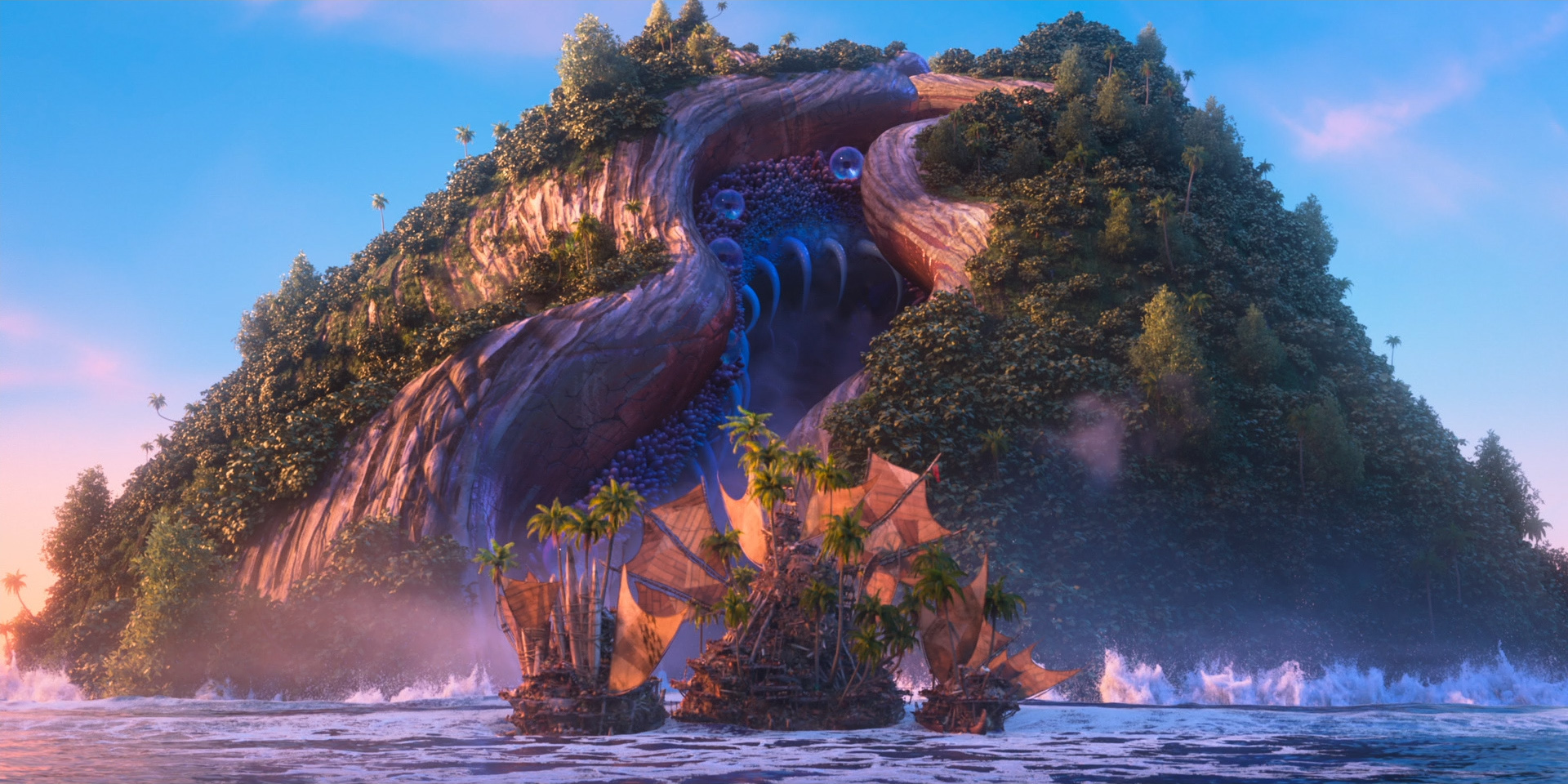

Disney Animation’s movie for 2025 is Zootopia 2, which is the studio’s 64th animated feature film. Zootopia 2 picks up where the first film left off, taking us deeper into the wonderful and wild animal world of the city. One of the really fun things about Zootopia projects is that each one expands the world further. The first film introduced the setting, the Zootopia+ series on Disney+ offered fun character vignettes to expand that world, and Zootopia 2 now takes us deep into the city’s history and to places both familiar and brand new. I’ve had a great time working on Zootopia 2 for the past two years!

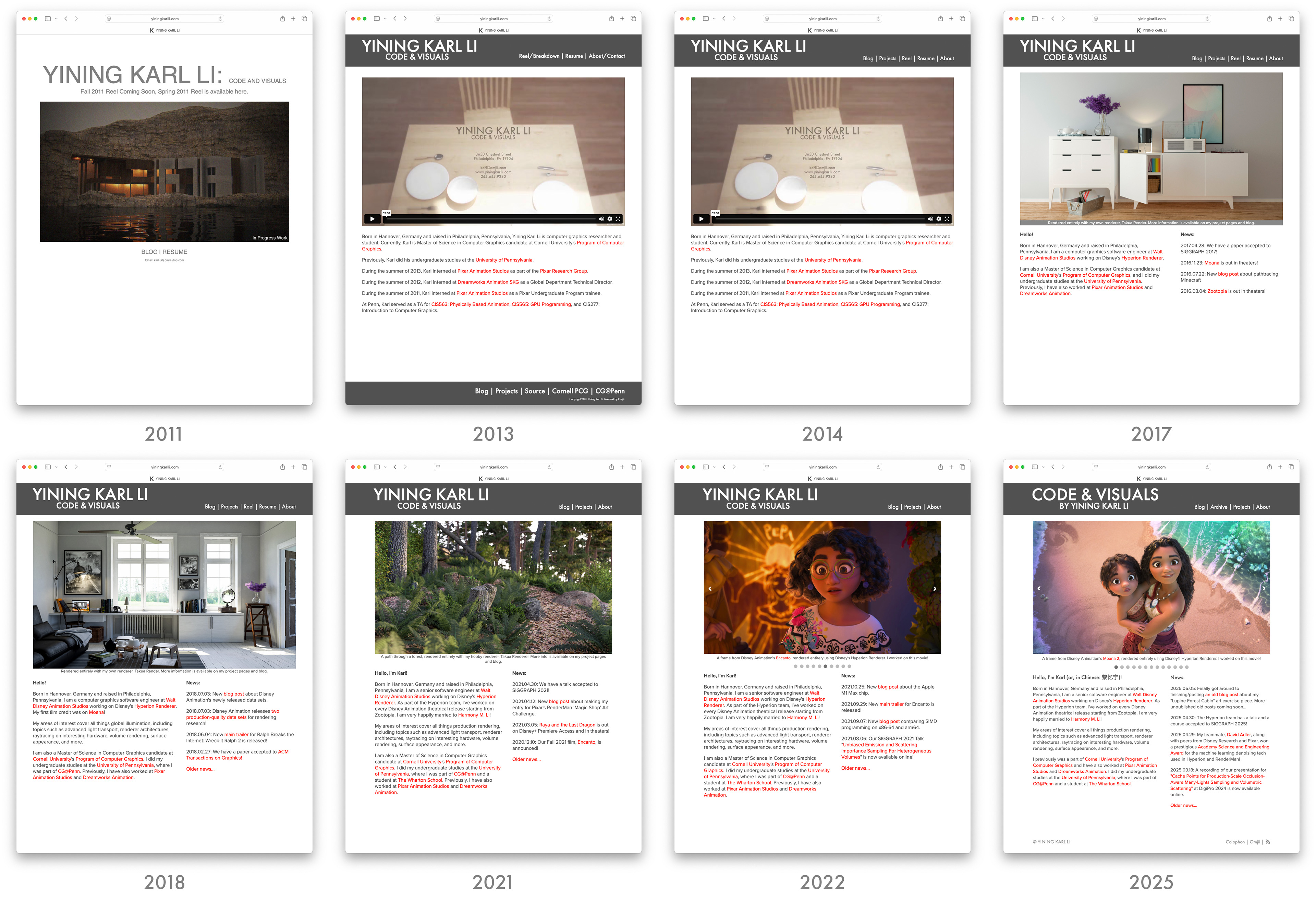

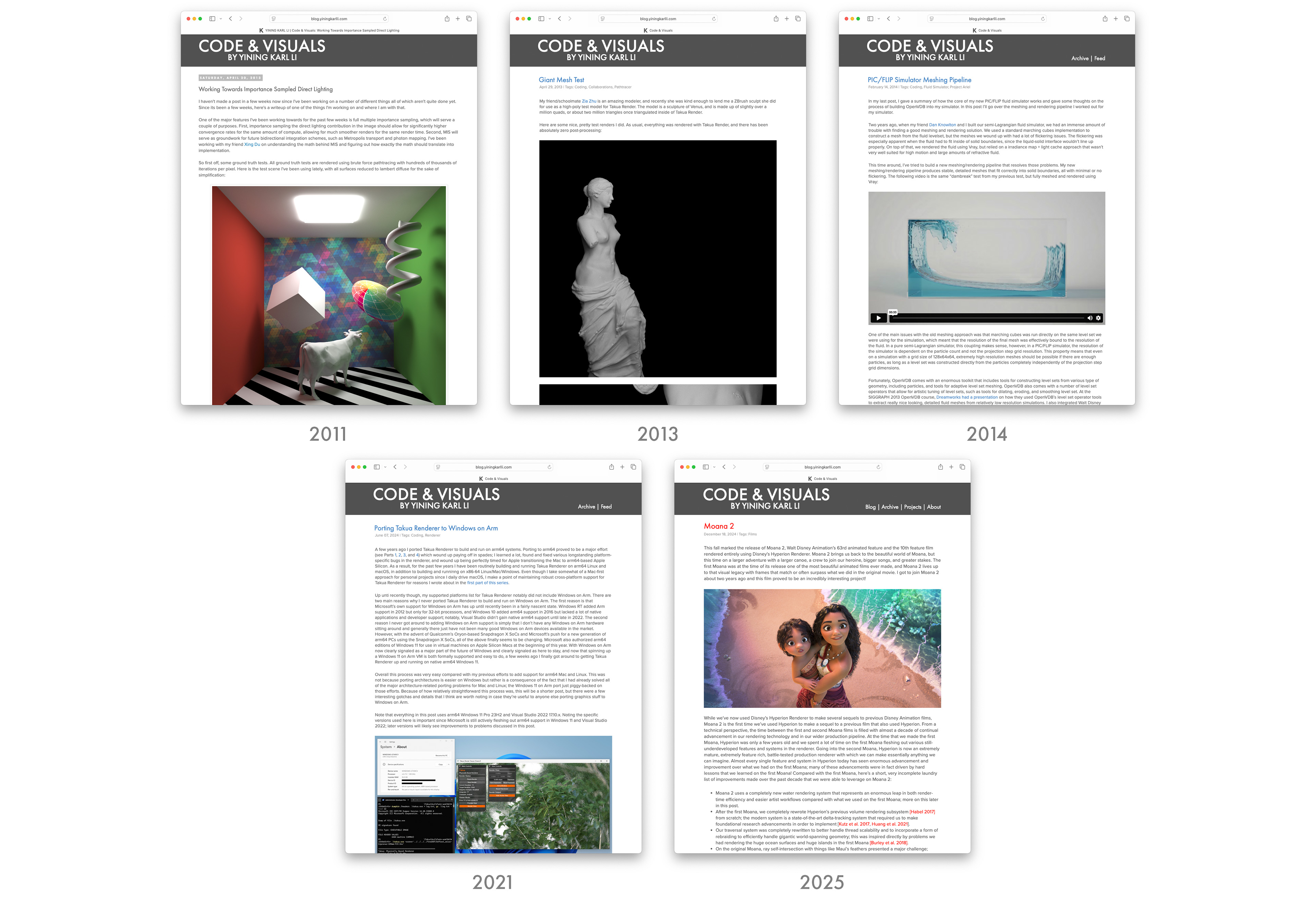

From a technology perspective, sequels are always interesting to work on because they give us the ability to evaluate where our filmmaking capabilities presently stand compared against a known past benchmark; we know roughly what it takes to make a Zootopia movie already, and so we can see how much better we have gotten at it in the intervening years. I think Zootopia 2 is an especially interesting case because of how important the first Zootopia (2016) was in the history of Disney Animation’s technology development. For a bit of context: the decade of Disney Animation films leading up to Zootopia (2016) was a time when the studio was rapidly climbing a steep learning curve for making CG movies. Every film had technical challenges that called for the studio to overcome unprecedented obstacles. Zootopia (2016) similarly presented an enormous list of challenges, but upon completing the film I felt there was a stronger sense of confidence in what the studio could achieve together. A small anecdote about Zootopia (2016) that I am very proud of is that at SIGGRAPH 2017, I heard from a friend at a major peer feature animation studio that they were blown away and had absolutely no idea how we had made Zootopia.

Ever since then, the sense in the studio has always been “this movie will be hard to make, but we know how to make it.” This isn’t to say that we don’t have interesting and difficult challenges to overcome in each movie we make; we always do! But, ever since Zootopia (2016)’s completion, I think we’ve been able to approach the challenges in each movie with greater confidence that we will be able to find solutions.

The major technology challenges on Zootopia 2 ultimately were pretty similar to the challenges on Zootopia (2016): everything is about detail and scale [Burkhard et al. 2016]. The world of Zootopia is incredibly detailed and visually rich, and that detail has to hold up at scales ranging from a tiny shrew to the tallest giraffe. Most characters are covered in detailed fur and hair, and because the setting is a modern city, shots can have hundreds or even thousands of characters on screen all at the same time, surrounded by all of the vehicles and lights and zillions of other props and details one expects in a city. Almost every shot in the movie has some form of complex simulation or FX work, and the nature of the story takes us through every environment and lighting scenario imaginable, all of which we have to be able to render cohesively and efficiently. Going back and rewatching Zootopia (2016), I still notice how much incredible geometry and shading detail is packed into every frame, and in the nine years since, our artists have only pushed things even further.

To give an example of the amazing amount of detail in Zootopia 2: at one point during production, our rendering team noticed some shots that had incredibly detailed snow with tons of tiny glints, so out of curiosity we opened up the shots to see how the artists had shaded the snow, and we found that they had constructed the snow out of zillions upon zillions of individual ice crystals. We were completely blown away; constructing snow this way was an idea that Disney Research had explored shortly after the first Frozen movie was made [Müller et al. 2016], but at the time it was purely a theoretical research idea, and a decade later our artists were just going ahead and actually doing it. The result in the final film looks absolutely amazing, and on top of that, instead of needing a specialized technology solution to make this approach feasible, in the past decade both our renderer and computers in general have gotten so much faster and our artists have improved their workflows so much that a brute-force solution was good enough to achieve this effect without much trouble at all.

One of the largest rendering advancements we made on Zootopia (2016) was the development of the Chiang hair shading model, which has since become the de-facto industry standard for fur/hair shading and is implemented in most major production renderers. For Zootopia 2, we kept the Chiang hair shading model [Chiang et al. 2016] as-is, but instead put a lot of effort into improving the accuracy and performance of our hair ray-geometry intersection algorithms. Making improvements to our ray-curve intersector actually took a large amount of close iteration with our Look Development artists. This may sound surprising since we didn’t change the fur shader at all, but the final look of our fur is an effect that arises from extensive multiple-scattering between fur strands, for which small energy differences that arise from inaccuracies in ray-curve intersection can multiply over many bounces into pretty significant overall look differences. In an original film, if the look of a character’s hair drifts slightly during early preproduction due to underlying renderer changes, generally these small visual changes can be tolerated and factored in as the look of the film evolves, but in a sequel with established characters that have a known target look that we must meet, we have to be a lot more careful.

I’ve been lucky enough to have gotten to work on a wide variety of types and scales of projects over the past decade at Disney Animation, and for Zootopia 2 I got to work on two of my absolute favorite types of projects. The first type of favorite project is the ones where we get to work on a custom solution for a very specific visual need in the film; these are the projects where I can point out a specific thing in final frames that is there because I wrote the code for it. My second type of favorite project is ones where we get to take something super bleeding edge from pure research and take it all the way through to practical, wide production usage. Getting to do both of these types of projects on the same film was a real treat! On Zootopia 2, working on the water tubes sequence was the first project type, and working closely with Disney Research Studios to widely deploy our next-generation path guiding system was the second project type. Hopefully we’ll have a lot more to present on both of these at SIGGRAPH/DigiPro 2026, but in the meantime here’s a quick summary.

One of the big projects I worked on for Moana 2 was a total, from-scratch rethink of our entire approach to rendering water. For the most part the same system we used on Moana 2 proved to be equally successful on Zootopia 2, but for the sequence where Nick, Judy, and Gary De’Snake zoom across the city in a water tube transport system, we had to extend the water rendering system from Moana 2 a little bit further. During this sequence, our characters are inside of glass tubes filled with water moving at something like a hundred miles per hour, with the surrounding environment visible through the tubes and whizzing by. In order to achieve the desired art direction, the tubes had to be modeled with actual water geometry inside since things like bubbles and sloshes and murk and such had to be visible, so going from inside to outside the geometry we had to render was characters inside of water inside of double-sided glass tubes set in huge complex forest and city environments. To both give artists the ability to efficiently model this setup and efficiently render these shots, we wound up building out a customized version of the standard nested dielectrics solution [Schmidt and Budge 2002]. Normally nested dielectrics is pretty straightforward to implement in a simple academic renderer (I’ve written about implementing nested dielectrics in my hobby renderer before), but implementing nested dielectrics to work correctly with the myriad of other advanced features in a production renderer while also remaining performant and robust within the context of a wavefront path tracing architecture proved to require a bit more work compared with in a toy renderer.

During Moana 2’s production, we started work with Disney Research|Studios on a next-generation path guiding system in Hyperion that supports both volumes and surfaces (unlike our previous path guiding system, which only supported surfaces); this new system is built on top of the excellent and state-of-the-art Open Path Guiding (OpenPGL) library [Herholz and Dittebrandt 2022]. Zootopia 2 is the first film where we’ve been able to deploy our next-generation path guiding on a wide scale, rendering about 12% of the entire movie using this system. We presented a lot of the technical details of this new system in our course on path guiding [Reichardt et al. 2025] at SIGGRAPH 2025, but a lot more work beyond what we presented in that course had to go into making path guiding a really production scalable renderer feature. This effort required deep collaboration between a handful of developers on the Hyperion team and a bunch of folks at Disney Research|Studios, to the point where over the past few years Disney Research|Studios has been using Hyperion essentially as one of their primary in-house research renderer platforms and Disney Research staff have been working directly with us on the same codebase. Having come from a more academic rendering background, I think this is one of the coolest things that being part of the larger Walt Disney Company enables our team and studio to do. Our next-generation path guiding system proved to be a really valuable tool on Zootopia 2; in several parts of the movie, entire sequences that we had anticipated to be extraordinarily difficult to render saw enormous efficiency and workflow improvements thanks to path guiding and wound up going through with relative ease!

One particularly fun thing about working on Zootopia 2 was that my wife, Harmony Li, was one of the movie’s Associate Technical Supervisors; this title means she was one of the leads for Zootopia 2’s TD department. Harmony being a supervisor on the show meant I got to work closely with her on a few things! She oversaw character look, simulation, technical animation, crowds, and something that Disney Animation calls “Tactics”, which is essentially optimization across the entire show ranging from pipeline and workflows all the way to render efficiency. As part of Zootopia 2’s Tactics strategy, the rendering team was folded more closely into the asset building process than in previous shows. Having huge crowds of thousands of characters on screen meant that every single individual character needed to be as optimized as possible, and to that end the rendering team helped provide guidance and best practices early in the character modeling and look development process to try to keep everything optimized while not compromising on final look. However, render optimization was only a small part of making the huge crowds in Zootopia 2 possible; various production technology teams and the TD department put enormous groundbreaking work into developing new ways to efficiently author and represent crowd rigs in USD and to interactively visualize huge crowds covered in fur inside of our 3D software packages. All of this also had to be done while, for the first time on a feature film project, Disney Animation switched from Maya to Presto for animation, and all on a movie which by necessity contains by far the greatest variety of different rig types and characters in any of our films (possible in any animated film, period). Again, more on all of this at SIGGRAPH 2026, hopefully.

I think all of the things I’ve written about in this post are just a few great examples of why I think having a dedicated in-house technology development team is so valuable to the way we make films- Disney Animation’s charter is to always be making animated films that push the limits of the art form, and making sure our films are the best looking films we can possibly make is a huge part of that goal. As an example, while Hyperion has a lot of cool features and unique technologies that are custom tailored to support Disney Animation’s needs and workflows, in my opinion the real value Hyperion brings at the end of the day is that our rendering team partners extremely closely with our artists and TDs to build exactly the tools that are needed for each of our movies, with maximum flexibility and customization since we know and develop the renderer from top to bottom. This is true of every technology team at Disney Animation, and it’s a big part of why I love working on our movies. I’ve written only about the projects I worked directly on in this post, which is a tiny subset of the whole of what went into making this movie. Making Zootopia 2 took dozens and dozens of these types of projects to achieve, and I’m so glad to have gotten to be a part of it!

On another small personal note, my wife and I had our first kid during the production of Zootopia 2, and our baby’s name is in the credits in the production babies section. What a cool tradition, and what a cool thing that our baby will forever be a part of!

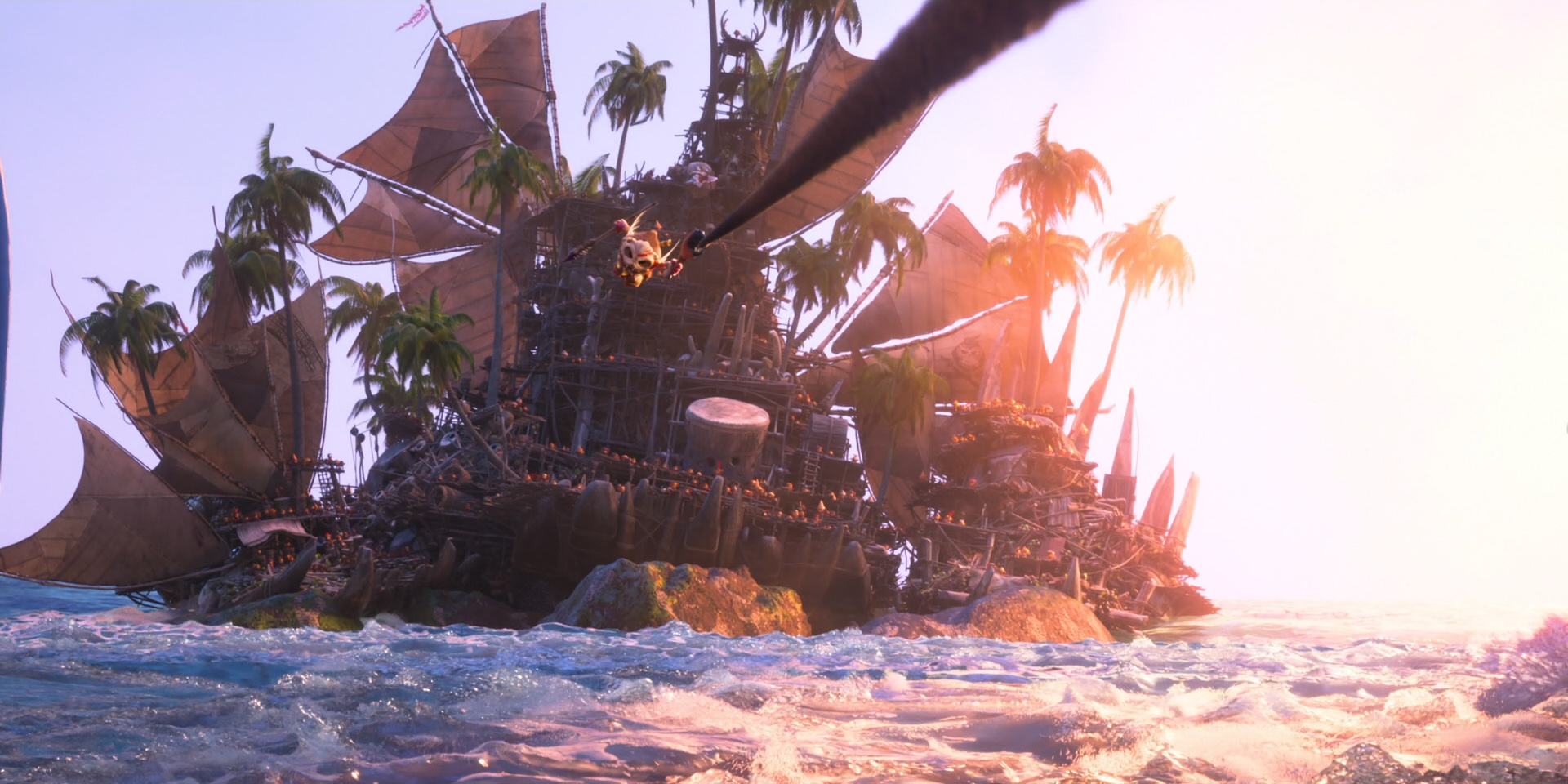

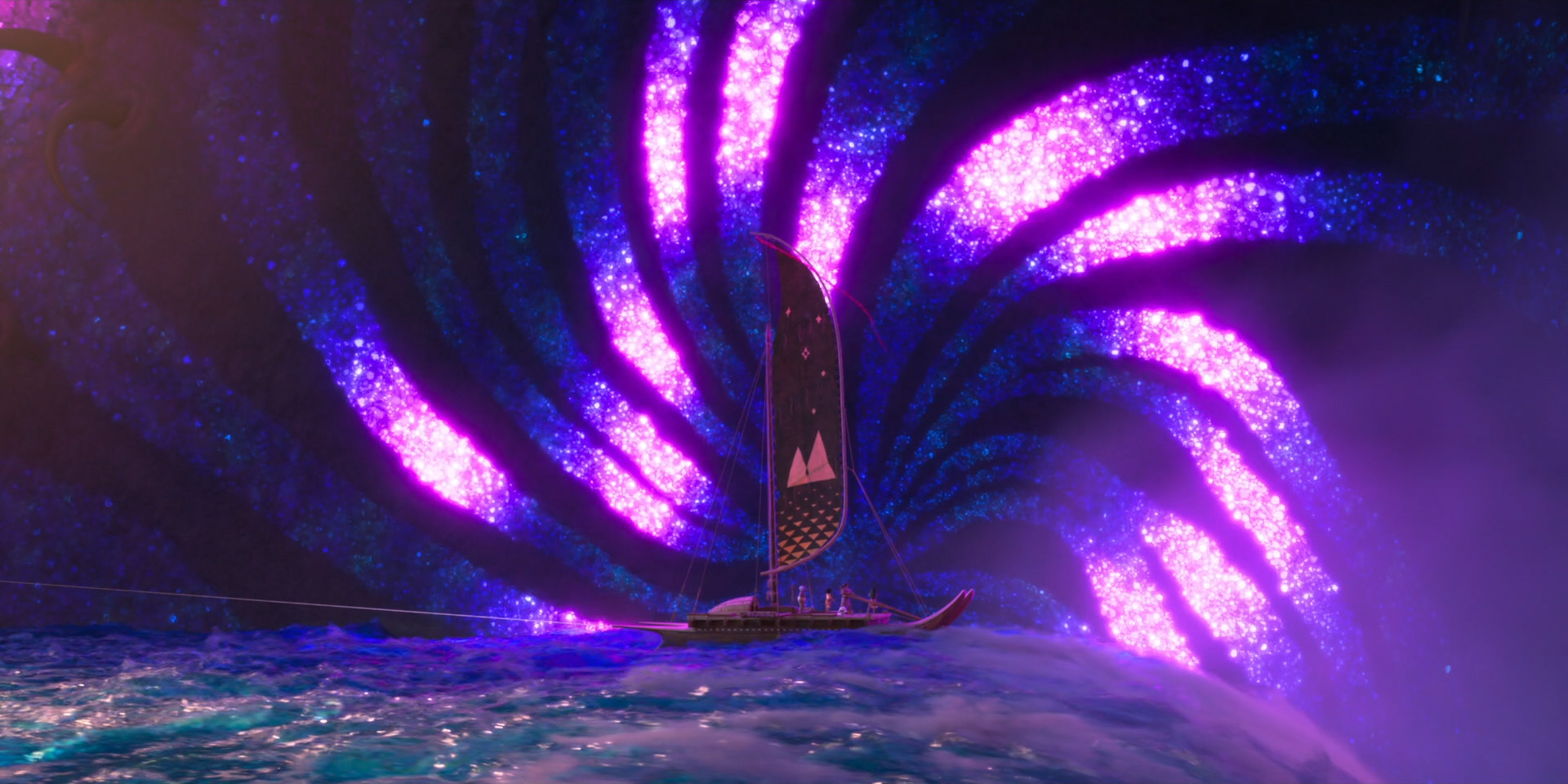

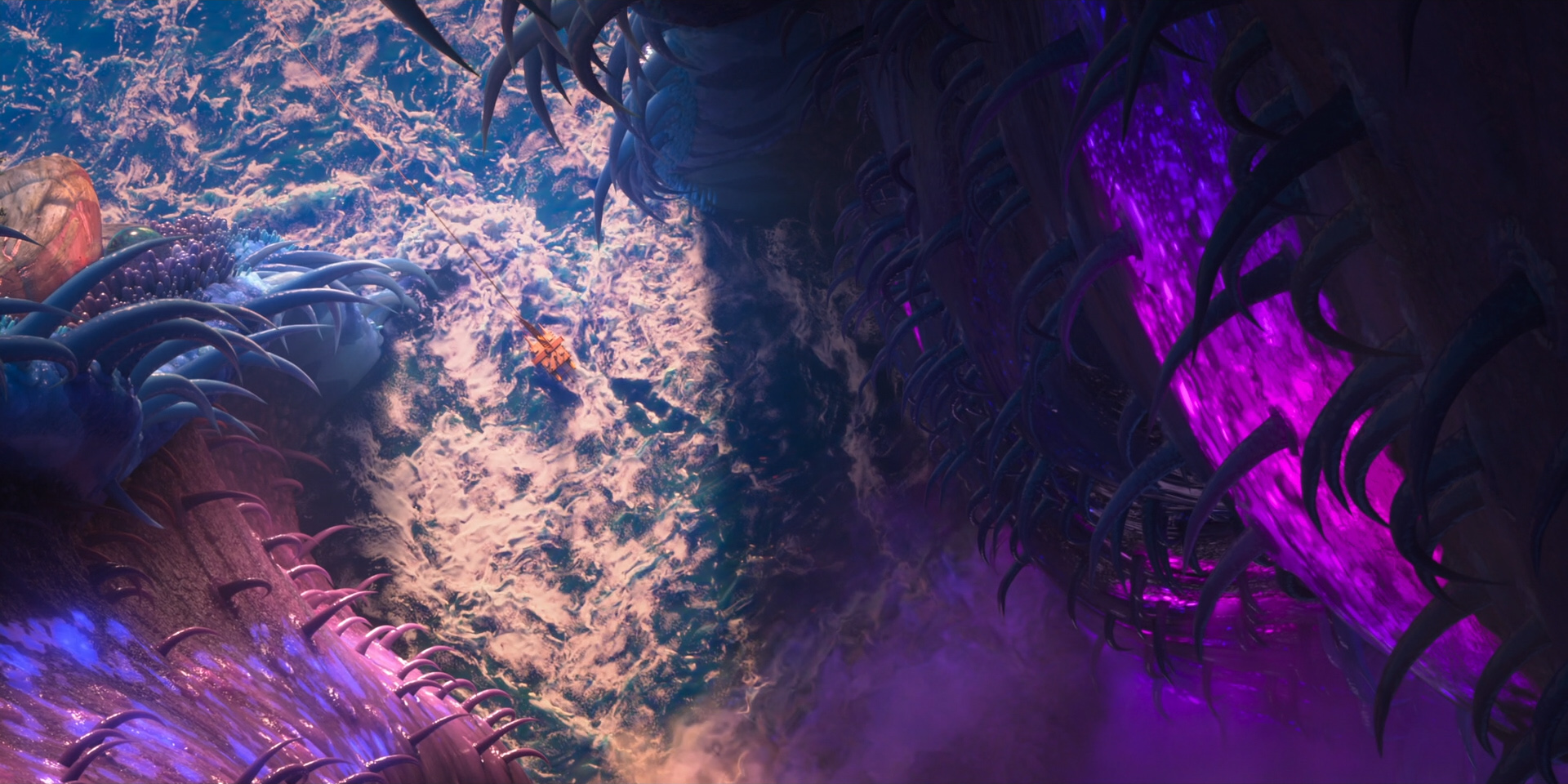

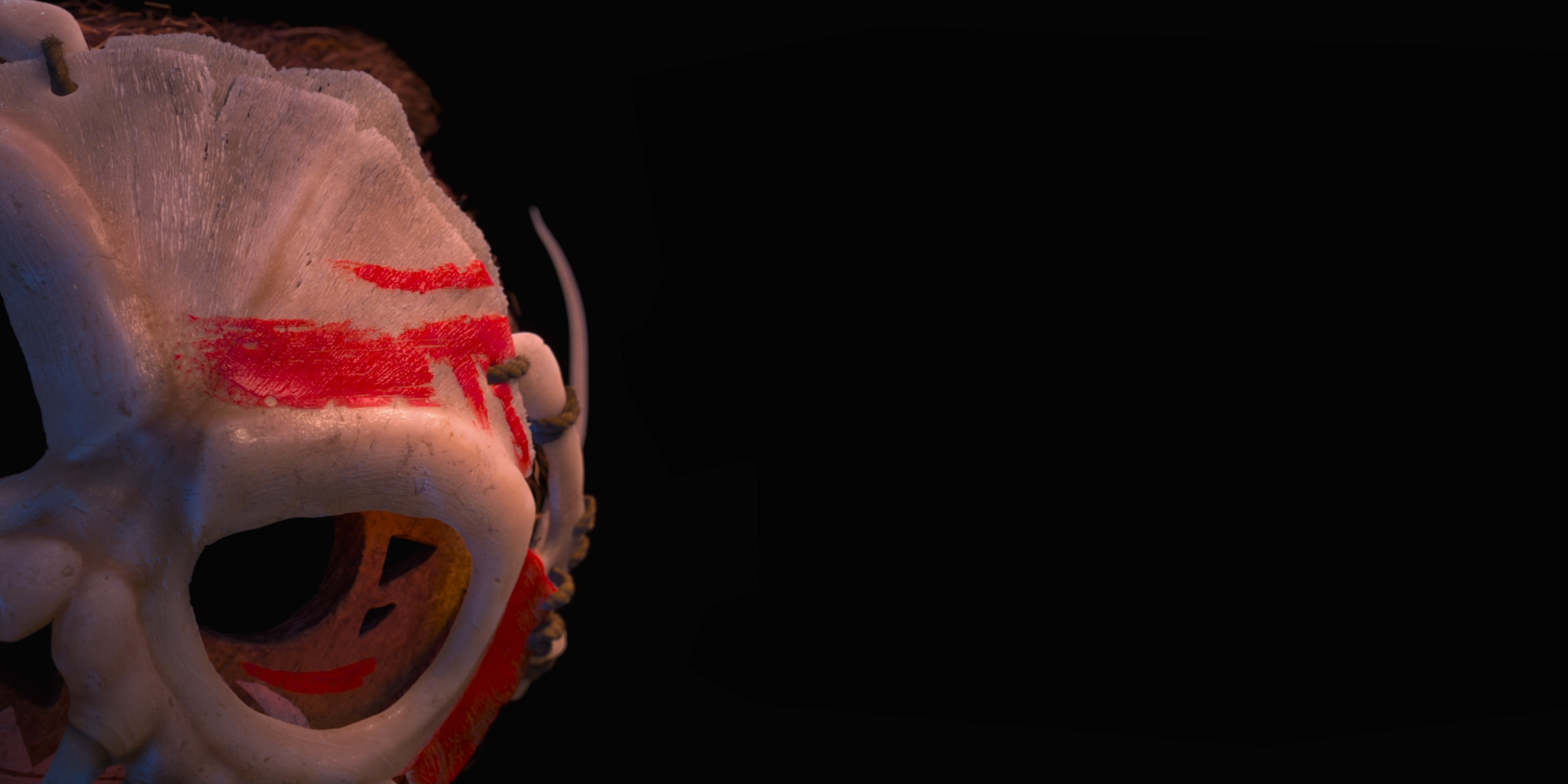

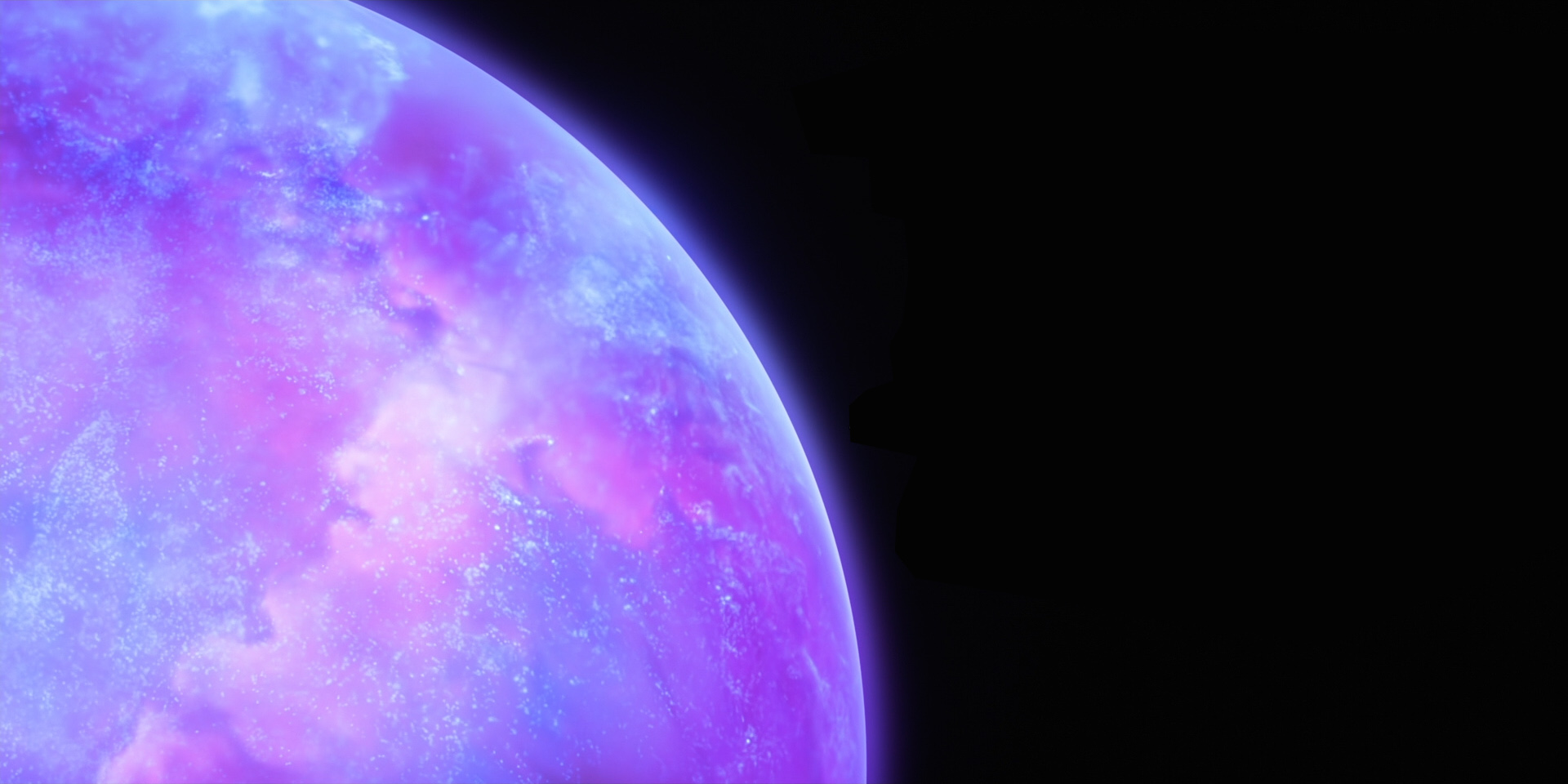

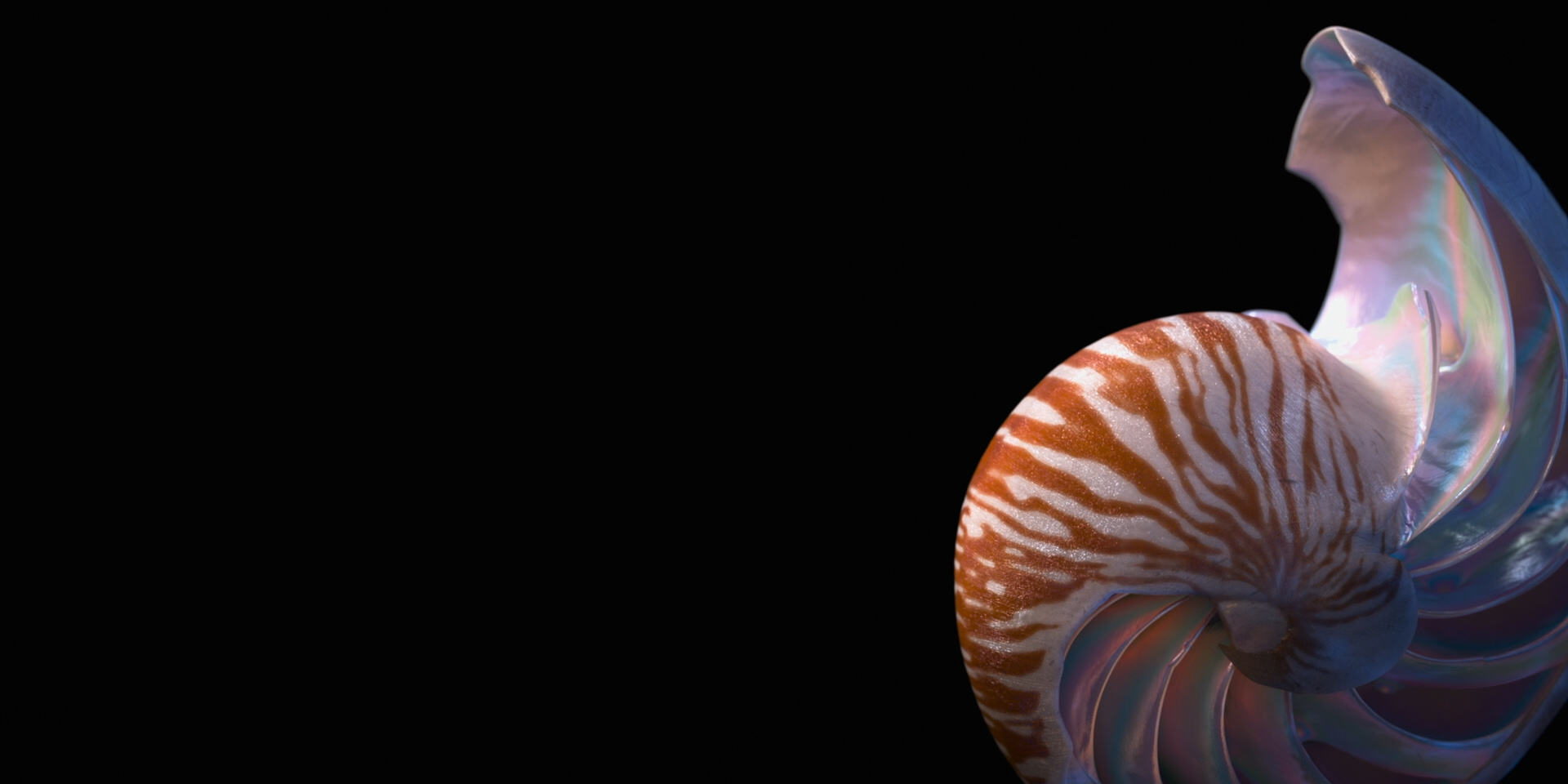

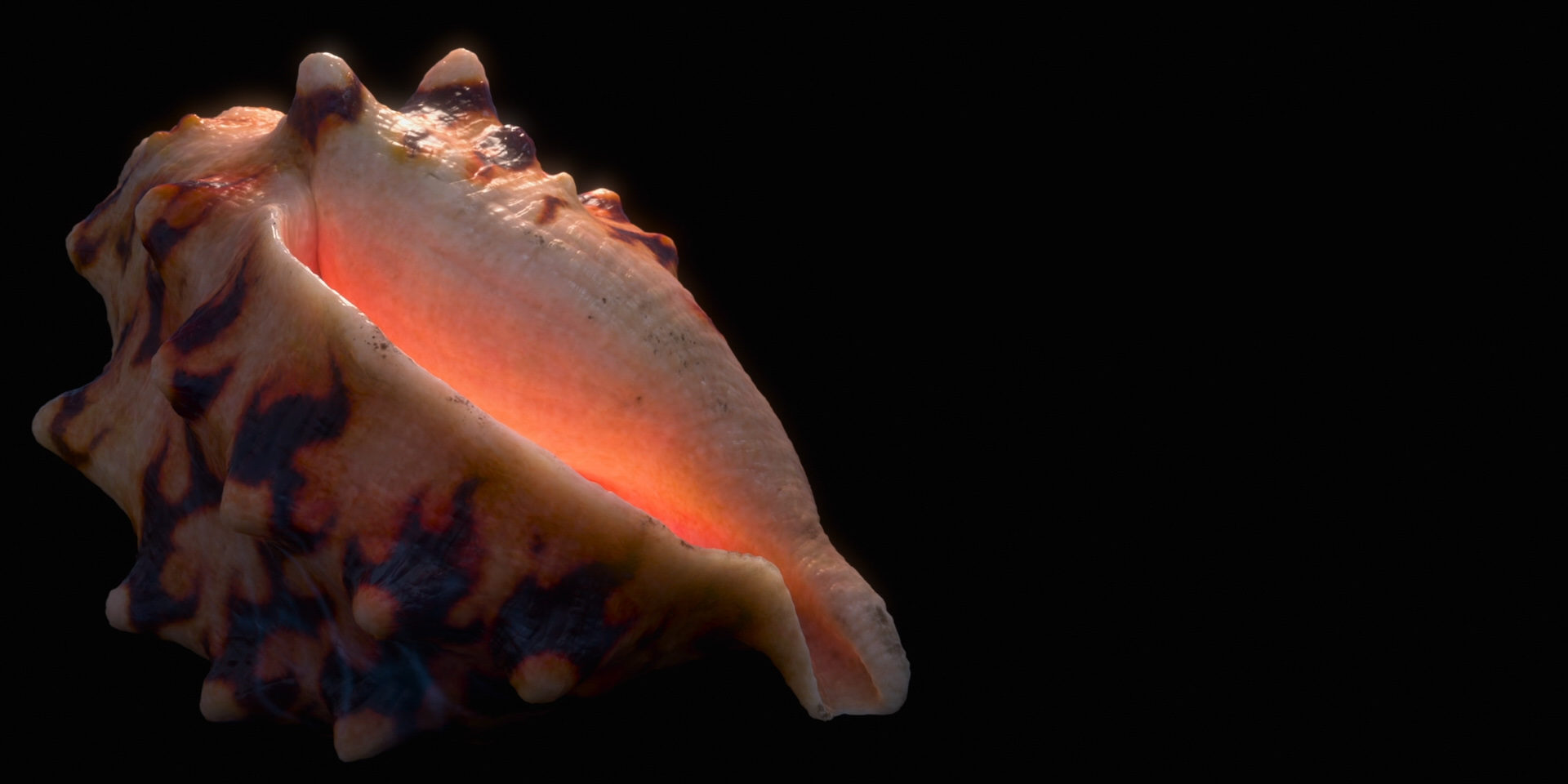

Below are some beautiful frames from Zootopia 2. Every last detail in this movie was hand-crafted by hundreds of artists and TDs and engineers out of a dedication to and love for animation as an art form, and I promise this movie is worth seeing on the biggest theater screen you can find!

All images in this post are courtesy of and the property of Walt Disney Animation Studios.

References

Nicholas Burkard, Hans Keim, Brian Leach, Sean Palmer, Ernest J. Petti, and Michelle Robinson. 2016. From Armadillo to Zebra: Creating the Diverse Characters and World of Zootopia. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2016 Production Sessions. Article 24.

Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang, Benedikt Bitterli, Chuck Tappan, and Brent Burley. 2016. A Practical and Controllable Hair and Fur Model for Production Path Tracing. Computer Graphics Forum (Proc. of Eurographics) 35, 2 (May 2016), 275-283.

Sebastian Herholz and Addis Dittebrandt. 2022. Intel® Open Path Guiding Library.

Thomas Müller, Marios Papas, Markus Gross, Wojciech Jarosz, and Jan Novák. 2016. Efficient Rendering of Heterogeneous Polydisperse Granular Media. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH Asia) 35, 6 (Nov. 2016), Article 168.

Lea Reichardt, Brian Green, Yining Karl Li, and Marco Manzi. 2025. Path Guiding Surfaces and Volumes in Disney’s Hyperion Renderer- A Case Study. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2025 Course Notes: Path Guiding in Production and Recent Advancements. 30-66.

Charles M. Schmidt and Brian Budge. 2002. Simple Nested Dielectrics in Ray Traced Images. Journal of Graphics Tools 7, 2 (Jan. 2002), 1–8.