Moana 2

This fall marked the release of Moana 2, Walt Disney Animation’s 63rd animated feature and the 10th feature film rendered entirely using Disney’s Hyperion Renderer. Moana 2 brings us back to the beautiful world of Moana, but this time on a larger adventure with a larger canoe, a crew to join our heroine, bigger songs, and greater stakes. The first Moana was at the time of its release one of the most beautiful animated films ever made, and Moana 2 lives up to that visual legacy with frames that match or often surpass what we did in the original movie. I got to join Moana 2 about two years ago and this film proved to be an incredibly interesting project!

While we’ve now used Disney’s Hyperion Renderer to make several sequels to previous Disney Animation films, Moana 2 is the first time we’ve used Hyperion to make a sequel to a previous film that also used Hyperion. From a technical perspective, the time between Moana and Moana 2 is filled with almost a decade of continual advancement in our rendering technology and in our wider production pipeline. At the time that we made the first Moana, Hyperion was only a few years old and we spent a lot of time on the first Moana fleshing out various still-underdeveloped features and systems in the renderer. Going into Moana 2, Hyperion is now an extremely mature, extremely feature rich, battle-tested production renderer with which we can make essentially anything we can imagine. Almost every single feature and system in Hyperion today has seen enormous advancement and improvement over what we had on the first Moana; many of these advancements were in fact driven by hard lessons that we learned on the first Moana! Compared with the first Moana, here’s a short, very incomplete laundry list of improvements made over the past decade that we were able to leverage on Moana 2:

- Moana 2 uses a completely new water rendering system that represents an enormous leap in both render-time efficiency and easier artist workflows compared with what we used on the first Moana; more on this later in this post.

- After the first Moana, we completely rewrote Hyperion’s previous volume rendering subsystem [Habel 2017] from scratch; the modern system is a state-of-the-art delta-tracking system that required us to make foundational research advancements in order to implement [Kutz et al. 2017, Huang et al. 2021].

- Our traversal system was completely rewritten to better handle thread scalability and to incorporate a form of rebraiding to efficiently handle gigantic world-spanning geometry; this was inspired directly by problems we had rendering the huge ocean surfaces and huge islands in the first Moana [Burley et al. 2018].

- On the original Moana, ray self-intersection with things like Maui’s feathers presented a major challenge; Moana 2 is the first film using our latest ray self-intersection prevention system that notably does away with any form of ray bias values.

- We introduced a limited form of photon mapping on the first Moana that only worked between the sun and water surfaces [Burley et al. 2018].; Moana 2 uses an evolved version of our photon mapper that supports all of our light types, many or our standard lighting features, and even has advanced capabilities like a form of spectral dispersion.

- We’ve made a number of advancements [Burley et al. 2017, Chiang et al. 2016, Chiang at al. 2019, Zeltner et al. 2022] to various elements of the Disney BSDF shading model.

- Subsurface scattering on the first Moana was done using normalized diffusion; since then we’ve moved all subsurface scattering to use a state-of-the-art brute force path tracing approach [Chiang et al. 2016].

- Eyes on the first Moana used our old ad-hoc eye shader; eyes on Moana 2 use our modern physically plausible eye shader that includes state-of-the-art iris caustics calculated using manifold next event estimation [Chiang & Burley 2018].

- The emissive mesh importance sampling system that we implemented on the first Moana and our overall many-lights sampling system has seen many efficiency improvements [Li et al. 2024].

- Hyperion has gained many more powerful features granting artists an enormous degree of artistic control both in the renderer and post-render in compositing [Burley 2019, Burley et al. 2024].

- Since the first Moana, Hyperion’s subdivision/tessellation system has gained an advanced fractured mesh system that makes many of the huge-scale effects in the first Moana movie much easier for us to create today [Burley & Rodriguez 2022].

- We’ve introduced path guiding into Hyperion to handle particularly difficult light transport cases [Müller et al. 2017, Müller 2019].

- The original Moana used our somewhat ad-hoc first-generation denoiser, while Moana 2 uses our best-in-industry, Academy Award winning1 second-generation deep learning denoiser jointly developed by Disney Research Studios, Disney Animation, Pixar, and ILM [Vogels et al. 2018, Dahlberg et al. 2019].

- Even Hyperion’s internal architecture has changed enormously; Hyperion originally was famous for being a batched wavefront renderer, but this has evolved significantly since then and continues to evolve.

There are many many more changes to Hyperion that there simply isn’t room to list here. To give you some sense of how far Hyperion has evolved between Moana and Moana 2: the Hyperion used on Moana was internally versioned as Hyperion 3.x; the Hyperion used on Moana 2 is internally versioned as Hyperion 16.x, with each version number in between representing major changes. In addition to improvements in Hyperion, our rendering team has also been working for the past few years on a next-generation interactive lighting system that extensively leverages hardware GPU ray tracing; Moana 2 saw the widest deployment yet of this system. I can’t say much more on this topic yet, but we’ve started to publish bits and pieces of work from this project, such as how we’ve created a new realtime ray tracing GPU Ptex implementation [Lee et al. 2025].

Of course, there are also still parts of Hyperion that have more or less remained exactly the same as they were during the original Moana; these parts of the renderer have stood the test of time and proven to be reliable foundational pieces of the Disney Animation filmmaking process. A great example is the fur/hair shading model [Chiang et al. 2016] that was originally developed for Zootopia and used on human characters for the first time in Moana. Even though our hair simulation continues to advance with every movie [Kaur et al. 2025], it turns out that the Chiang fur/hair model has been so reliable thaat we haven’t really had to change it since, and in fact it has since become a de-facto standard across the entire graphics industry!

Outside of the rendering group, literally everything else about our entire studio production pipeline has changed as well; the first Moana was made mostly on proprietary internal data formats, while Moana 2 was made using the latest iteration [Zhuang 2025] of our cutting-edge modern USD pipeline [Miller et al. 2022, Vo et al. 2023, Li et al. 2024]. The modern USD pipeline has granted our pipeline many amazing new capabilities and far more flexibility, to the point where it became possible to move our entire lighting workflow to a new DCC [Endo et al. 2025, Joseph and Butt 2025] for Moana 2 without needing to blow up the entire pipeline. Our next-generation interactive lighting system is similarly made possible by our modern USD pipeline. The modern pipeline has also allowed us to continue to push the scale of our films ever larger, with the ever-growing complexity of our crowds [Ros and Berriz 2025, Ros and Sullivan 2025] being a particular standout.

While I get to work on every one of our feature films and get to do fun and interesting things every time, Moana 2 is the most direct and deep I’ve worked on one of our films probably since the original Moana. There are two specific projects I worked on for Moana 2 that I am particularly proud of: a completely new water rendering system that is part of Moana 2’s overall new water FX workflow, and the volume rendering work that was done for the storm battle in the movie’s third act.

On the original Moana, we had to develop a lot of custom water simulation and rendering technology because commercial tools at the time couldn’t quite handle what the movie required. On the simulation side, the original Moana required Disney Animation to invent new techniques such as the APIC (affine particle-in-cell) fluid simulation model [Jiang et al. 2015] and the FAB (fluxed animated boundary) method for integrating procedural and simulated water dynamics [Stomakhin and Selle 2017]. Disney Animation’s general philosophy towards R&D is that we will develop and invent new methods when needed, but will then aim to publish our work with the goal of allowing anything useful we invent to find its way into the wider graphics field and industry; a great outcome is when our publications are adopted by the commercial tools and packages that we build on top of. APIC and FAB were both published and have since become a part of the stock toolset in Houdini, which in turn allowed us to build more on top of Houdini’s built-in SOPs for Moana 2’s water FX workflow.

On the rendering side, the main challenge on the original Moana for rendering water was the need to combine water surfaces from many different sources (procedural, manually animated, and simulated) into a single seamless surface that could be rendered with proper refraction, internal volumetric effects, caustics, and so on. Our solution to combine different water surfaces on the original Moana was to convert all input water elements into signed distance fields, composite all of the signed distance fields together into a single world-spanning levelset, and then mesh that levelset into a triangle mesh for ray intersection [Palmer et al. 2017]. While this process produced great visual results, running this entire world-spanning levelset compositing and meshing operation at renderer startup for each frame proved to be completely untenable due to how slow it made interaction for artists, so an extensive system for pre-caching ocean surfaces overnight to disk had to be built out. All in all, the water rendering and caching system on the first Moana required a dedicated team of over half a dozen developers and TDs to maintain, and setting up the levelset compositing system correctly proved to be challenging for artists.

For Moana 2, we decided to revisit water rendering with the goal of coming up with something much easier for artists to use, much faster to render, and much easier to maintain by a smaller group of engineers and TDs. Over the course of about half a year, we completely replaced the old levelset compositing and meshing system with a new ray-intersection-time CSG system. Our new system requires almost zero work for artists to set up, requires zero preprocessing time before renderer startup and zero on-disk caching, renders with negligible impact on ray tracing speed, and required zero dedicated TDs and only part of my time as an engineer to support once primary development was completed. In addition to all of the above, the new system also allows for both better looking and more memory efficient water because the level of detail that water meshes have to exist at is no longer constrained by the resolution of a world-size meshed levelset, even with an adaptive levelset meshing. I think this was a great example where by revisiting a world that we already knew how to make, we were given an opportunity to reevaluate what we learned on Moana in order to come up with something better by every metric for Moana 2.

We knew that returning to the world of Moana was likely going to require a heavy lift from a volume rendering perspective. With a mind towards this, we worked closely with Disney Research|Studios in Zürich to implement next-generation volume path guiding techniques in Hyperion [Reichardt et al. 2025], which wound up not seeing wide deployment this time but nonetheless proved to be a fun and interesting project from which we learned a lot. We also realized that the third act’s storm battle was going to be incredibly challenging from both an FX and rendering perspective; creating the storm battle required FX to invent whole new techniques [Rice 2025]! My last few months on Moana 2 were spent helping get the storm battle sequences finished; one extremely unusual thing we wound up doing was providing custom builds of Hyperion with specific optimizations tailored to the specific requirements of the storm sequence, sometimes going as far as to provide specific builds and settings tailored on a per-shot basis. Normally this is something any production rendering team tries to avoid if possible, but one of the benefits of having our own in-house team and our own in-house renderer is that we are still able to do this when the need arises. From a personal perspective, being able to point at specific shots and say “I wrote code for that specific thing” is pretty neat!

From both a story and a technical perspective, Moana 2 is everything we loved from Moana brought back, plus a lot of fun, big, bold new stuff [Bhatawadekar et al. 2025]. Making Moana 2 both gave us new challenges to solve and allowed us to revisit and come up with better solutions to old challenges from Moana. I’m incredibly proud of the work that my teammates and I were able to do on Moana 2; I’m sure we’ll have a lot more to share at SIGGRAPH 2025, and in the meantime I strongly encourage you to see Moana 2 on the biggest screen you can find!

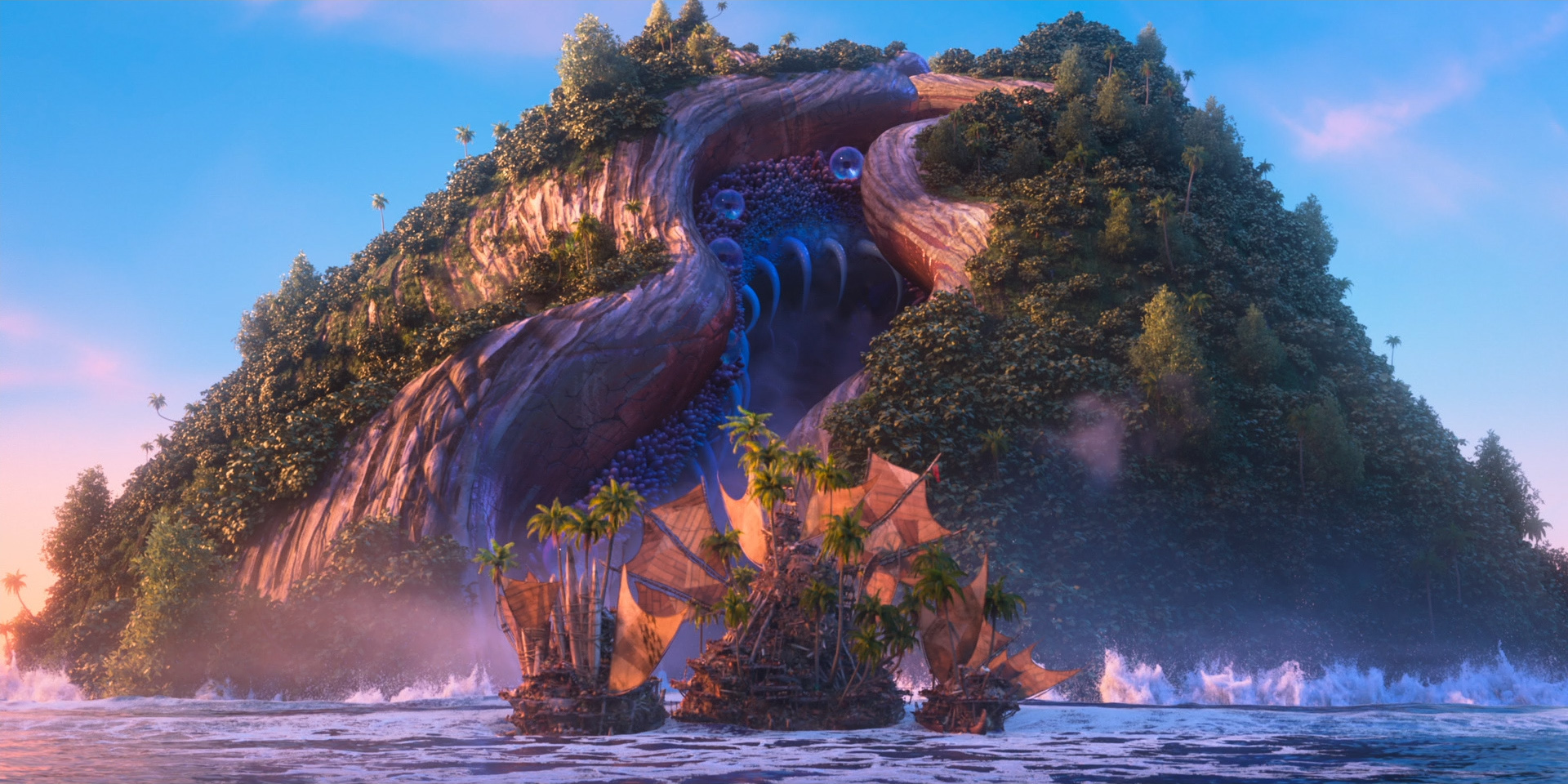

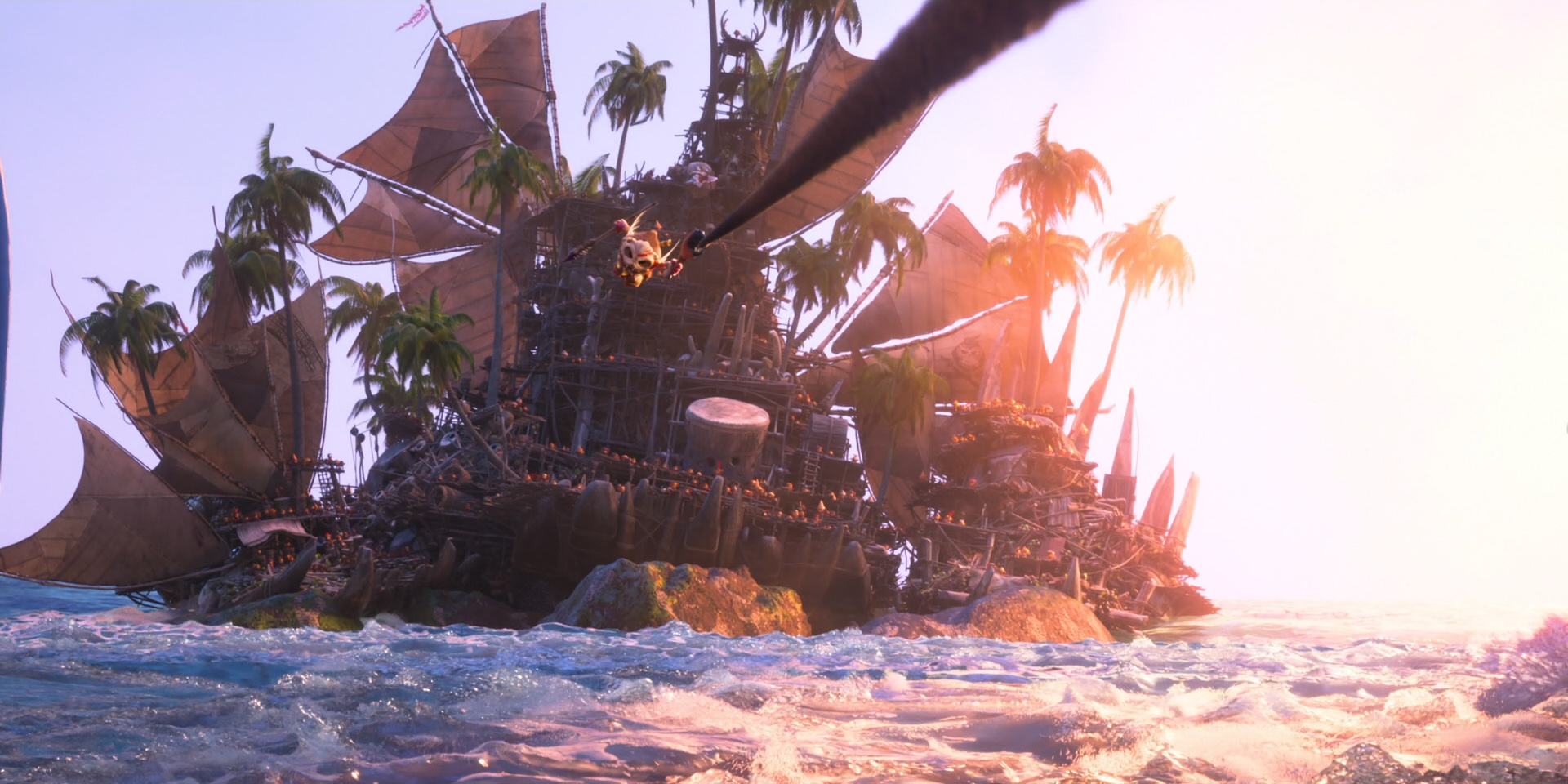

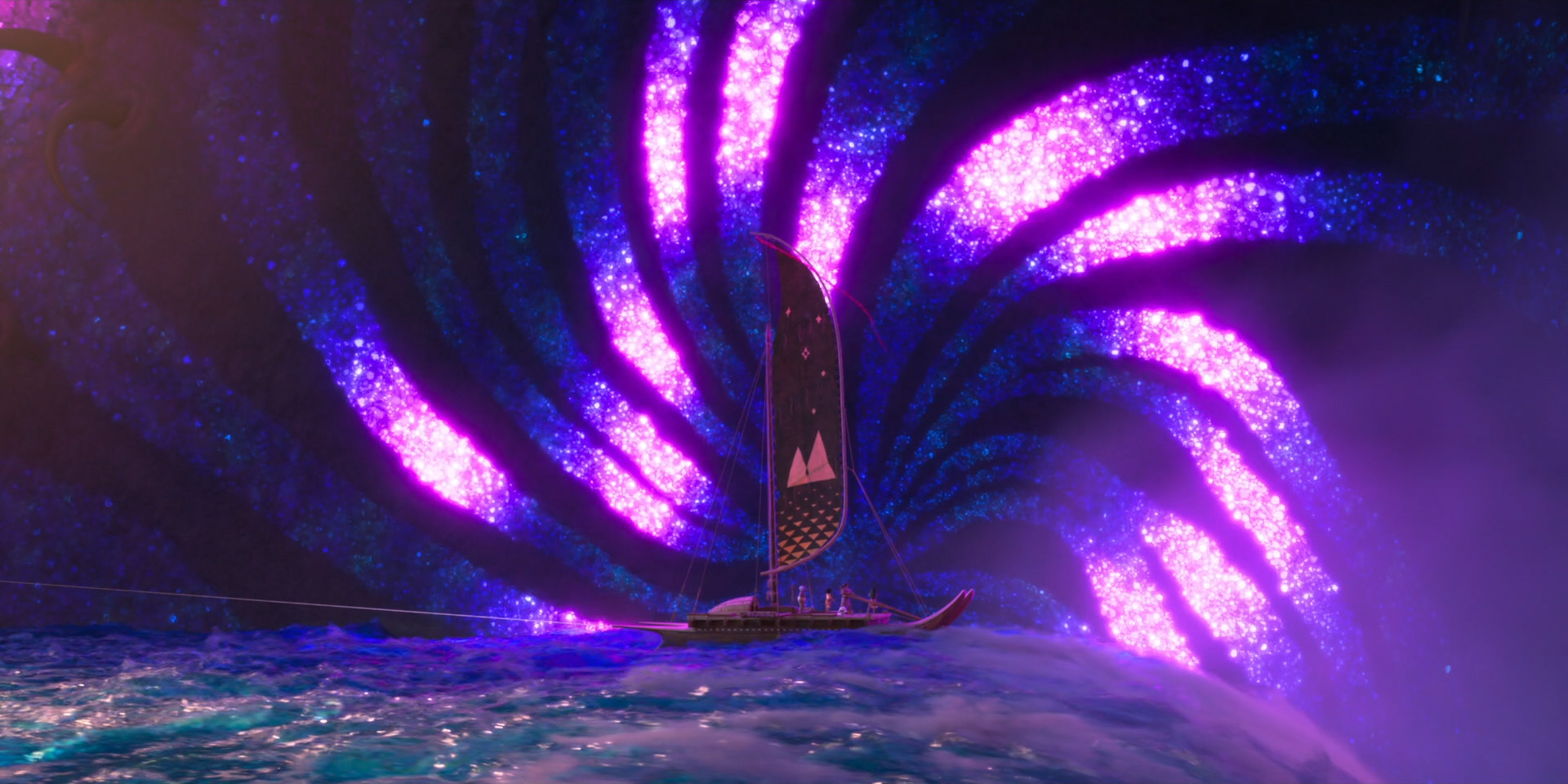

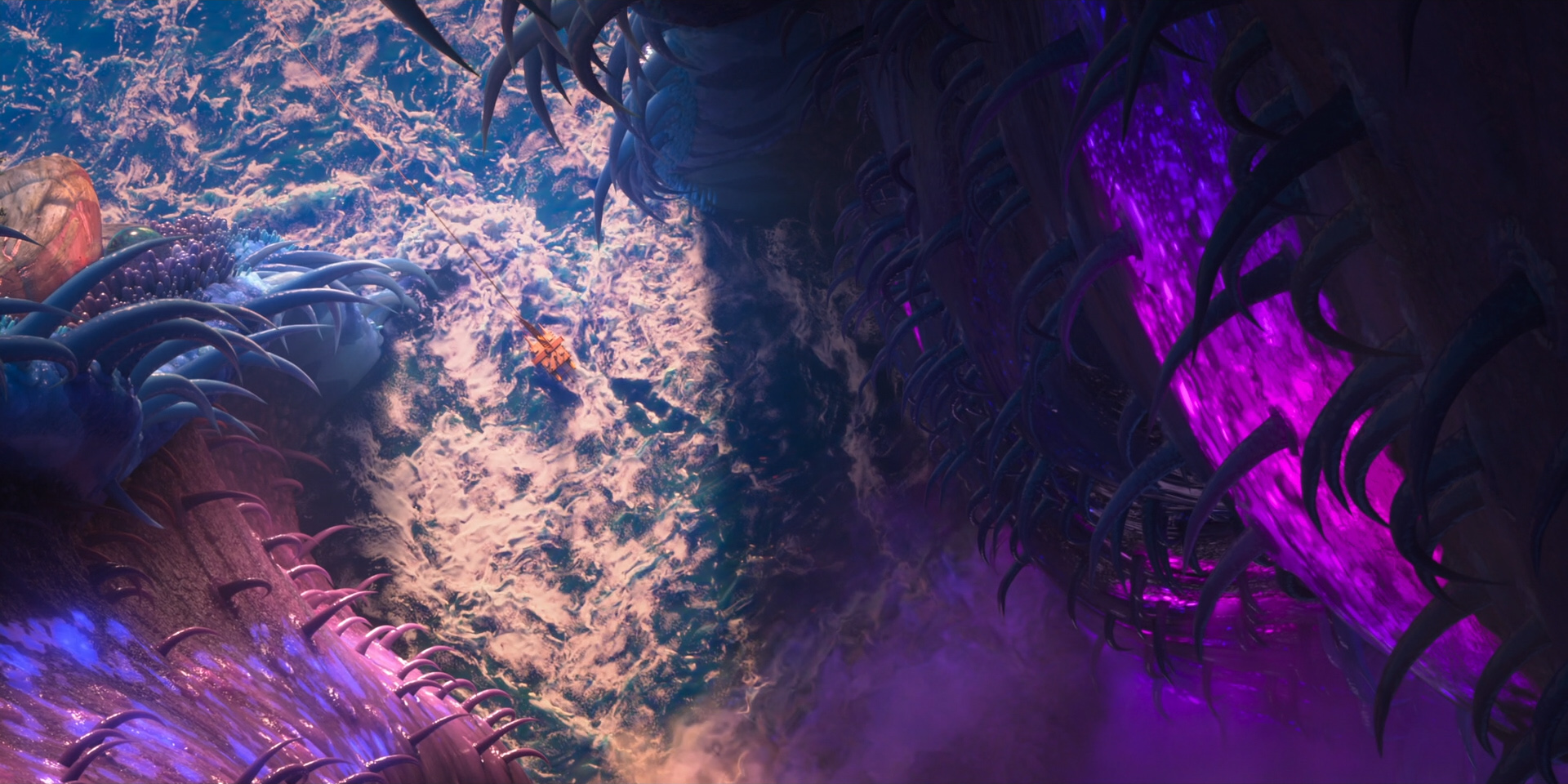

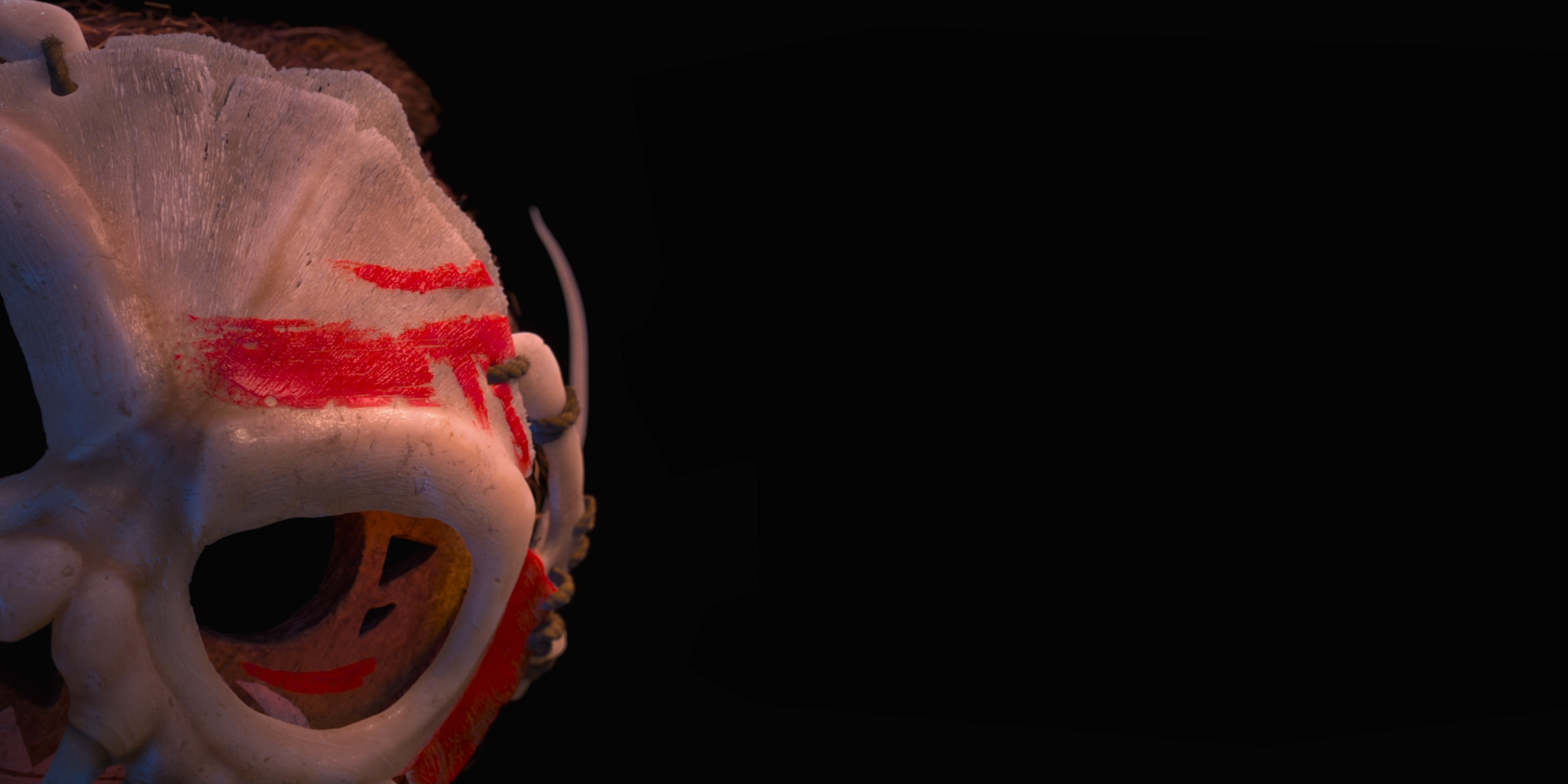

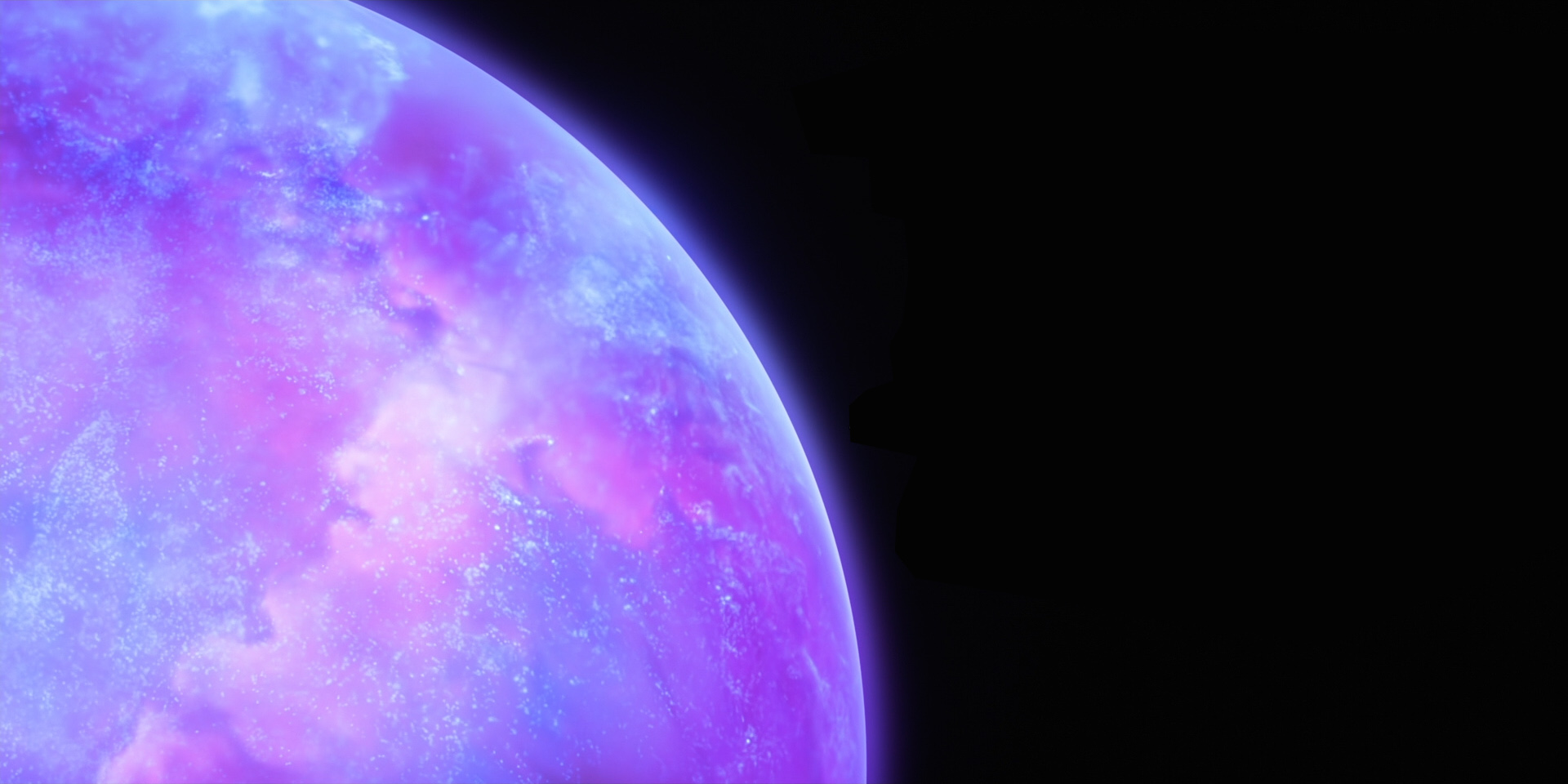

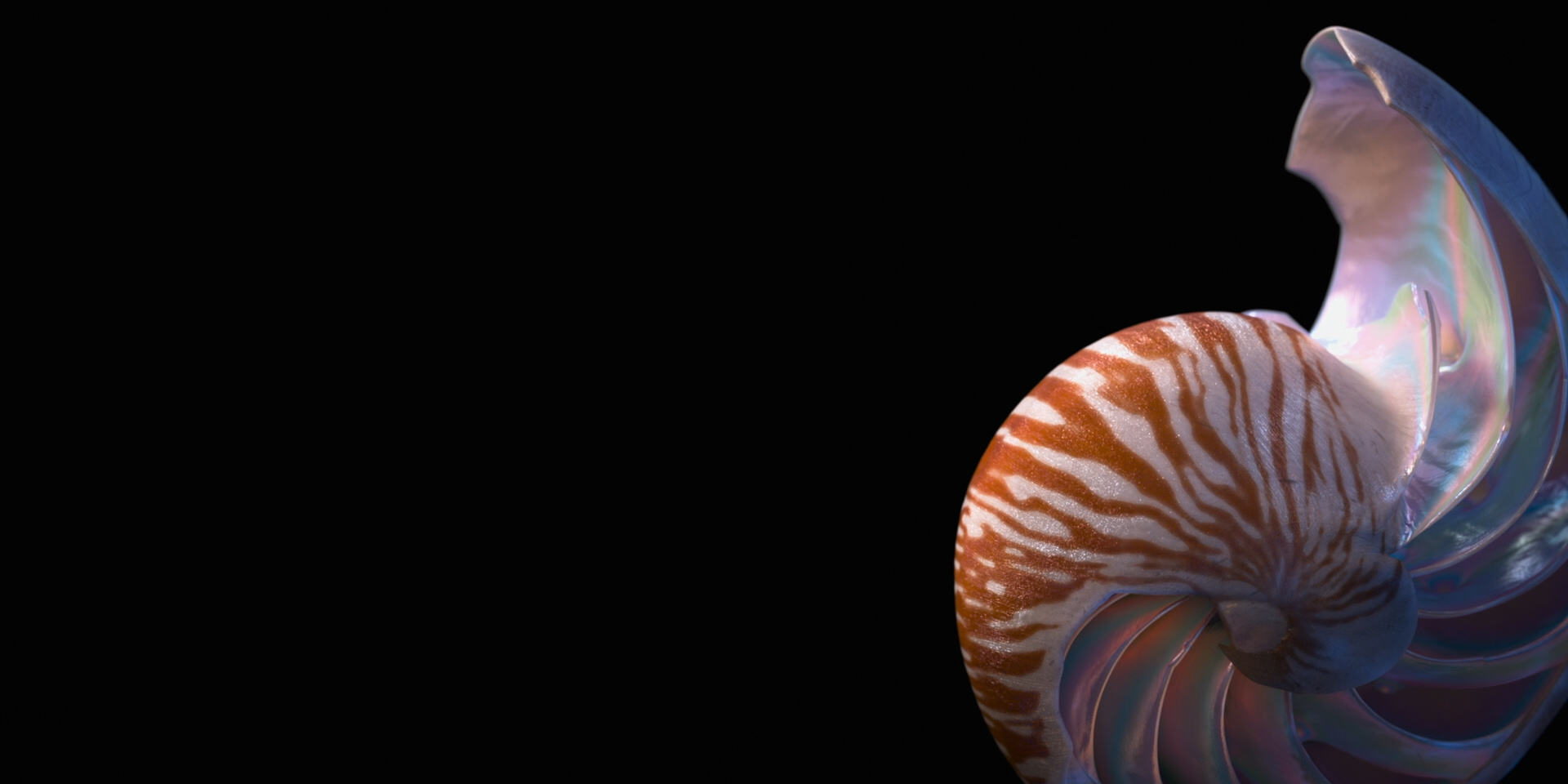

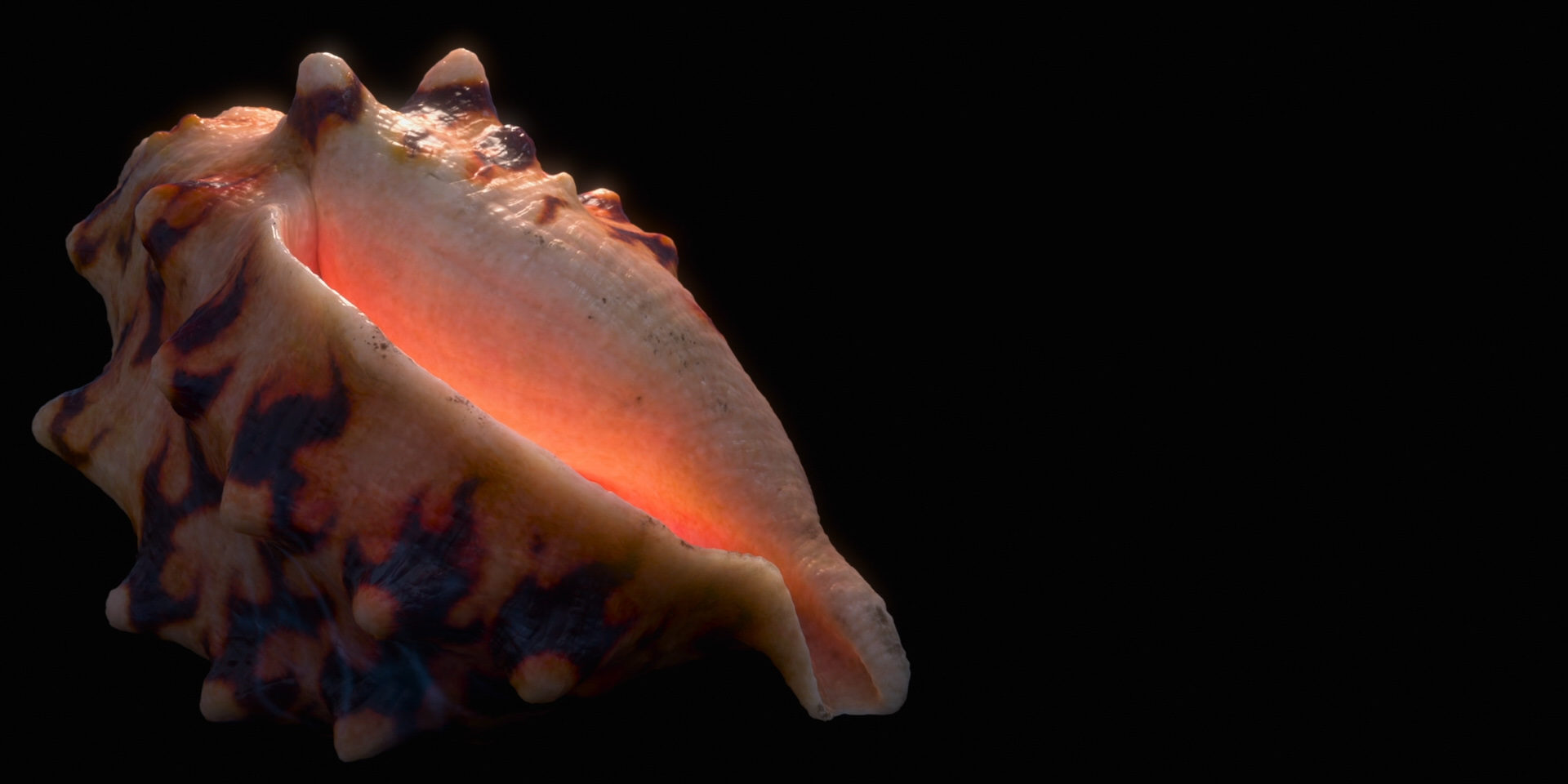

To give you a taste of how beautiful this film looks, here are some frames from Moana 2 from the Blu-ray, 100% created using Disney’s Hyperion Renderer by our amazing artists. These are presented in no particular order:

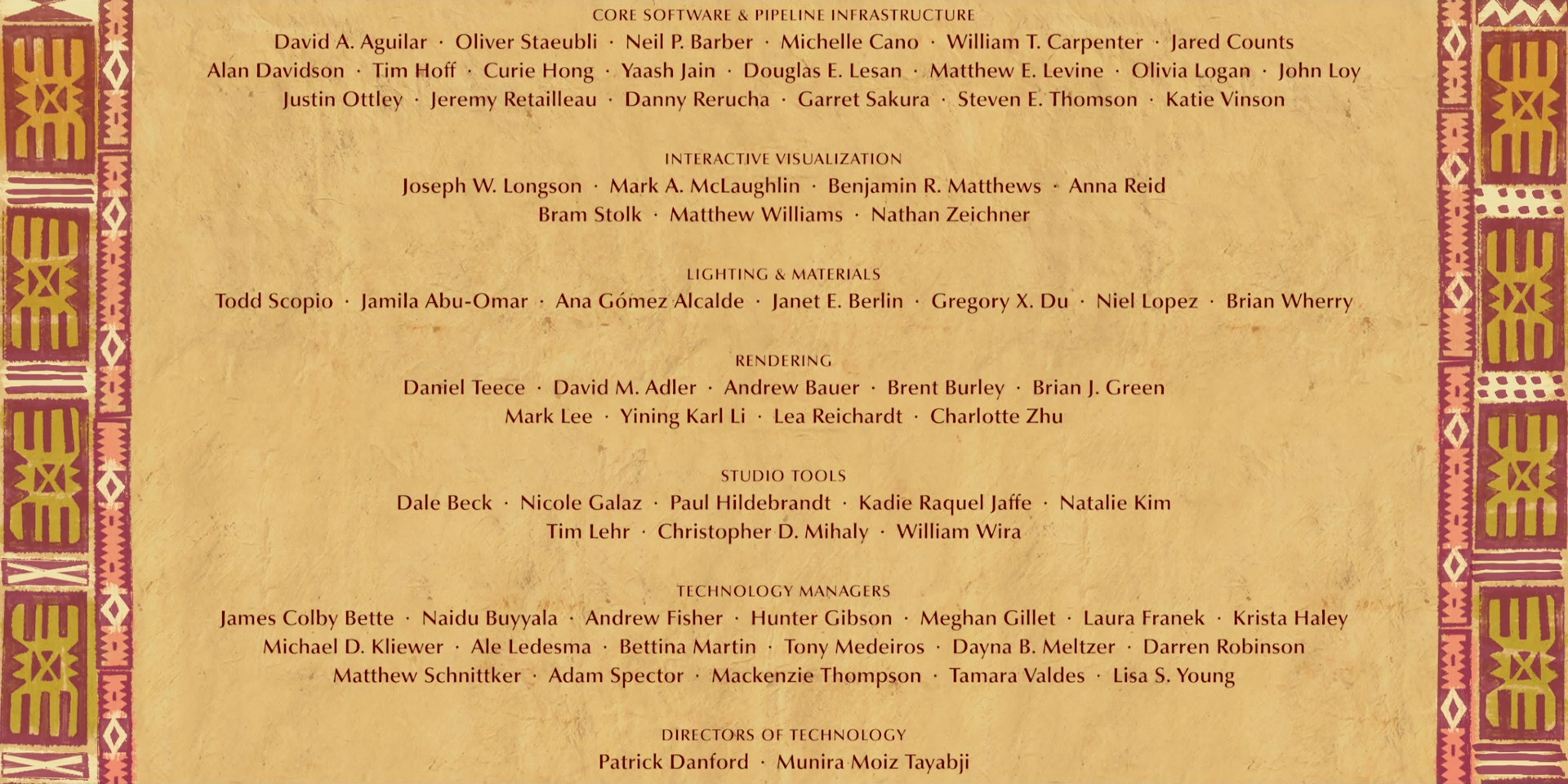

Here is the credits frame for the Hyperion team, along with several of the other teams that we work closely with to make rendering happen at Disney Animation. Specifically, the Lighting & Materials team develops our render translation pipeline and much of the artist-facing user interfaces in our lighting and shading tools, and the Interactive Visualization team is our sibling team that develops our in-house realtime rasterizer viewports.

All images in this post are courtesy of and the property of Walt Disney Animation Studios.

References

Sucheta Bhatawadekar, Behzad Mansoori-Dara, Adolph Lusinsky, and Rob Dressel. 2025. The Cinematography of Songs in Disney’s “Moana 2”. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2025 Talks. Article 64.

Brent Burley, David Adler, Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang, Ralf Habel, Patrick Kelly, Peter Kutz, Yining Karl Li, and Daniel Teece. 2017. Recent Advancements in Disney’s Hyperion Renderer. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2017 Course Notes: Path Tracing in Production Part 1. 26-34.

Brent Burley, David Adler, Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang, Hank Driskill, Ralf Habel, Patrick Kelly, Peter Kutz, Yining Karl Li, and Daniel Teece. 2018. The Design and Evolution of Disney’s Hyperion Renderer. ACM Transactions on Graphics 37, 3 (Jul. 2018), Article 33.

Brent Burley. 2019. On Histogram-Preserving Blending for Randomized Texture Tiling. Journal of Computer Graphics Techniques 8, 4 (Nov. 2019), 31-53.

Brent Burley and Francisco Rodriguez. 2022. Fracture-Aware Tessellation of Subdivision Surfaces. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2022 Talks. Article 10.

Brent Burley, Brian Green, and Daniel Teece. 2024. Dynamic Screen Space Textures for Coherent Stylization. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2024 Talks. Article 50.

Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang, Benedikt Bitterli, Chuck Tappan, and Brent Burley. 2016. A Practical and Controllable Hair and Fur Model for Production Path Tracing. Computer Graphics Forum (Proc. of Eurographics) 35, 2 (May 2016), 275-283.

Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang, Peter Kutz, and Brent Burley. 2016. Practical and Controllable Subsurface Scattering for Production Path Tracing. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2016 Talks. Article 49.

Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang and Brent Burley. 2018. Plausible Iris Caustics and Limbal Arc Rendering. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2018 Talks. Article 15.

Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang, Yining Karl Li, and Brent Burley. 2019. Taming the Shadow Terminator. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2019 Talks. Article 71.

Henrik Dahlberg, David Adler, and Jeremy Newlin. 2019. Machine-Learning Denoising in Feature Film Production. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2019 Talks. Article 21.

Colvin Kenji Endo, Norman Moses Joseph, Alex Nijmeh, and Todd Scopio. 2025. Prototype to Production: Building a Lighting Workflow in Houdini for Animation. In Proc. of Digital Production Symposium (DigiPro 2025). Article 3.

Ralf Habel. 2017. Volume Rendering in Hyperion. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2017 Course Notes: Production Volume Rendering. 91-96.

Wei-Feng Wayne Huang, Peter Kutz, Yining Karl Li, and Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang. 2021. Unbiased Emission and Scattering Importance Sampling for Heterogeneous Volumes. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2021 Talks. Article 3.

Chenfafu Jiang, Craig Schroeder, Andrew Selle, Joseph Teran, and Alexey Stomakhin. 2015. The Affine Particle-in-Cell Method. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH) 34, 4 (Aug. 2015), Article 51.

Norman Moses Joseph and Rehan Butt. 2025. The Design Opportunities of Moving to Houdini for Lighting with the world of Animation. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2025 Talks. Article 52.

Avneet Kaur, Hubert Leo, Nachiket Pujari, and Bret Bays. 2025. Choreography of Hair and Cloth in Disney’s “Moana 2”. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2025 Talks. Article 13.

Peter Kutz, Ralf Habel, Yining Karl Li, and Jan Novák. 2017. Spectral and Decomposition Tracking for Rendering Heterogeneous Volumes. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH) 36, 4 (Aug. 2017), Article 111.

Mark S. Lee, Nathan Zeichner, and Yining Karl Li. 2025. A Texture Streaming Pipeline for Real-Time GPU Ray Tracing. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2025 Talks. Article 12.

Harmony M. Li, George Rieckenberg, Neelima Karanam, Emily Vo, and Kelsey Hurley. 2024. Optimizing Assets for Authoring and Consumption in USD. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2024 Talks. Article 30.

Yining Karl Li, Charlotte Zhu, Gregory Nichols, Peter Kutz, Wei-Feng Wayne Huang, David Adler, Brent Burley, and Daniel Teece. 2024. Cache Points for Production-Scale Occlusion-Aware Many-Lights Sampling and Volumetric Scattering. In Proc. of Digital Production Symposium (DigiPro 2024). Article 6.

Tad Miller, Harmony M. Li, Neelima Karanam, Nadim Sinno, and Todd Scopio. 2022. Making Encanto with USD: Rebuilding a Production Pipeline Working from Home. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2022 Talks. Article 12.

Thomas Müller. 2019. Practical Path Guiding in Production. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2019 Course Notes: Path Guiding in Production. 37-50.

Thomas Müller, Markus Gross, and Jan Novák. 2017. Practical Path Guiding for Efficient Light-Transport Simulation. Computer Graphics Forum (Proc. of Eurographics Symposium on Rendering) 36, 4 (Jun. 2017), 91-100.

Sean Palmer, Jonathan Garcia, Sara Drakeley, Patrick Kelly, and Ralf Habel. 2017. The Ocean and Water Pipeline of Disney’s Moana. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2017 Talks. Article 29.

Lea Reichardt, Brian Green, Yining Karl Li, and Marco Manzi. 2025. Path Guiding Surfaces and Volumes in Disney’s Hyperion Renderer- A Case Study. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2025 Course Notes: Path Guiding in Production and Recent Advancements. 30-66.

Jacob Rice. 2025. Steerable Perlin Noise. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2025 Talks. Article 1.

Alberto J Luceño Ros and Cecilia Berriz. 2025. Creating the Mudskipper Pile in Disney’s “Moana 2”: A Slippery Problem Space. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2025 Talks. Article 63.

Alberto J Luceño Ros and Jeff Sullivan. 2025. The Art of Crowds Animation. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2025 Talks. Article 62.

Alexey Stomakhin and Andy Selle. 2017. Fluxed Animated Boundary Method. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH) 36, 4 (Aug. 2017), Article 68.

Emily Vo, George Rieckenberg, and Ernest Petti. 2023. Honing USD: Lessons Learned and Workflow Enhancements at Walt Disney Animation Studios. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2023 Talks. Article 13.

Thijs Vogels, Fabrice Rousselle, Brian McWilliams, Gerhard Röthlin, Alex Harvill, David Adler, Mark Meyer, and Jan Novák. 2018. Denoising with Kernel Prediction and Asymmetric Loss Functions. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH) 37, 4 (Aug. 2018), Article 124.

Tizian Zeltner, Brent Burley, and Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang. 2022. Practical Multiple-Scattering Sheen Using Linearly Transformed Cosines. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2022 Talks. Article 7.

Rikki Zhuang. 2025. Transitioning to an Explicit Dependency USD Asset Resolver. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2025 Course Notes: USD in Production. 73-106.

Footnotes

1 Our deep learning denoiser technology is one of the 2025 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Scientific and Engineering Award winners. keyboard_return