Over the next month and a half, I will be working on a pair of final projects for two of my classes, CIS565 (GPU Programming, taught by Patrick Cozzi), and CIS563 (Physically Based Animation, taught by Joe Kider).

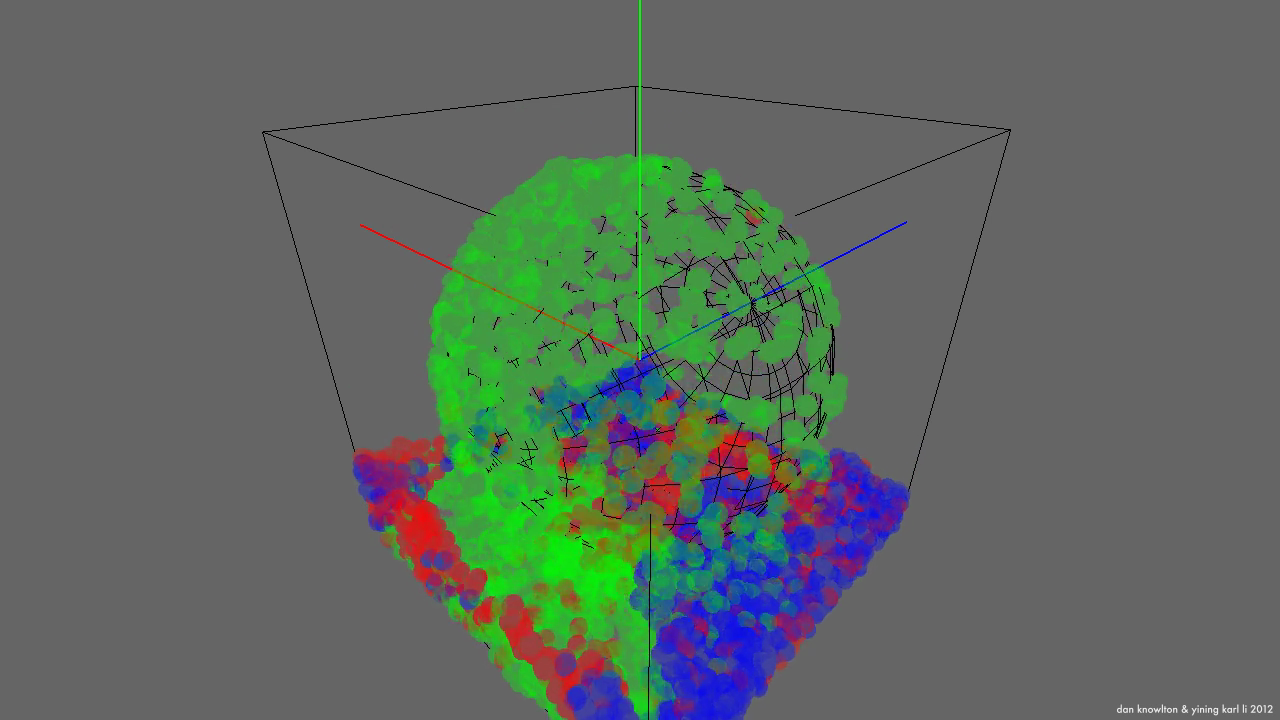

For CIS563, I will be teaming up with my fellow classmate and good friend Dan Knowlton to develop a liquid fluid simulator capable of simulating multiple fluids interacting against each other. Dan is without a doubt one of the best in our class and easily my equal or superior in all things graphics, so working with him should be a lot of fun. Our project is going to be based primarily on the paper Multiple Interacting Fluids by Losasso et. al. and as a starting point we will be using Chris Batty’s Fluid 3D framework.

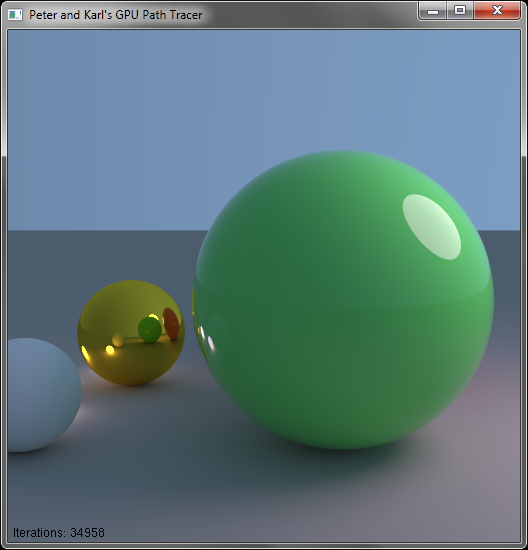

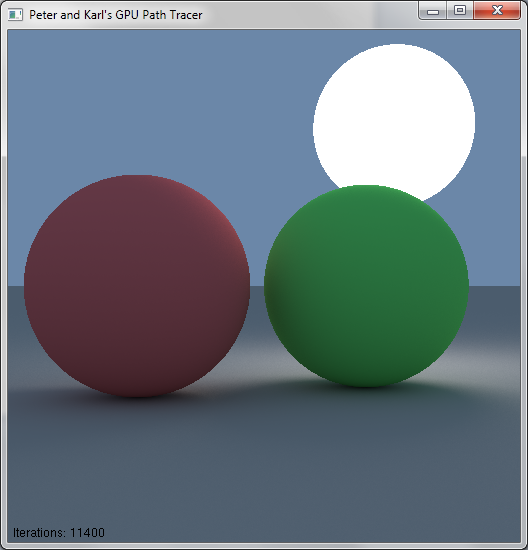

For CIS565, I will be working with my fellow Pixarian and friend Peter Kutz, who is somewhat of a physically based rendering titan at Penn. Working with Peter should be a very interesting and exciting learning experience. Peter and I will be developing a CUDA based GPU Pathtracer with the goal of generating convincing photorealistic images extremely rapidly. We will be developing our GPU pathtracer from scratch, although we will obviously draw inspiration from both Peter’s Photorealizer project and my own CPU pathtracer project.

For both projects, we will be keeping blogs where we will post development updates, so I won’t post too much about development details to this here personal blog. Instead, I’m thinking about posting a weekly digest of progress on both projects with links to interesting highlights on the project blogs.

Dan and I will be blogging at http://chocolatefudgesyrup.blogspot.com/. We’ve titled our project “Chocolate Syrup” for two reasons: firstly, Dan likes to codename his project with types of confectionaries, and secondly, chocolate syrup is one type of highly viscous fluid we aim for our simulator to be able to handle!

Peter and I will be blogging at http://gpupathtracer.blogspot.com/. For now we have decided to call our project “Peter and Karl’s GPU Pathtracer”, for obvious reasons.

Details for each project can be found in the first post of each blog, which are the project proposals.

Multiple Interacting Fluids Proposal: http://chocolatefudgesyrup.blogspot.com/2012/03/project-proposal.html

GPU Pathtracer Proposal: http://gpupathtracer.blogspot.com/2012/03/project-proposal.html

Both of these projects should be very very cool, and I’ll be posting often to both development blogs!