Ralph Breaks the Internet

The Walt Disney Animation Studios film for 2018 is Ralph Breaks the Internet, which is the sequel to 2012’s Wreck-It Ralph. Over the past two years, I’ve been fortunate enough to work on a number of improvements to Disney’s Hyperion Renderer for Ralph Breaks the Internet; collectively, these improvements make up perhaps the biggest jump in rendering capabilities that Hyperion has seen since the original deployment of Hyperion on Big Hero 6. I got my third Disney Animation credit on Ralph Breaks the Internet!

Over the past two years, the Hyperion team has publicly presented a number of major development efforts and research advancements. Many of these advancements were put into experimental use on Olaf’s Frozen Adventure last year, but Ralph Breaks the Internet is the first time we’ve put all of these new capabilities and features into full-scale production together. I was fortunate enough to be fairly deeply involved in several of these efforts (specifically, traversal improvements and volume rendering). One of my favorite things about working at Disney Animation is how production and technology partner together to make our films; we truly would not have been able to pull off any of Hyperion’s new advancements without production’s constant support and willingness to try new things in the name of advancing the artistry of our films.

Ralph Breaks the Internet is our first feature film to use Hyperion’s new spectral and decomposition tracking [Kutz et al. 2017] based null-collision volume rendering system exclusively. Originally we had planned to use the new volume rendering system side-by-side with Hyperion’s previous residual ratio tracking [Novák 2014] based volume rendering system [Fong 2017], but the results from the new system were so compelling that the show decided to switch over to the new volume rendering exclusively, which in turn allowed us to deprecate and remove the old volume rendering system ahead of schedule. This new volume rendering system is the culmination of two years of work from Ralf Habel, Peter Kutz, Patrick Kelly, and myself. We had the enormous privilege of working with a large number of FX and lighting artists to develop, test, and refine this new system; specifically, I want to call out Jesse Erickson, Henrik Falt, and Alex Nijmeh for really championing the new volume rendering system and encouraging and supporting its development. We also owe an enormous amount to the rest of the Hyperion development team, which gave us the time and resources to spent two years building a new volume rendering system essentially from scratch. Finally, I want to underscore that the research and underpins our new volume rendering system was conducted jointly between us and Disney Research Zürich, and that this could not have happened without our colleagues at Disney Research Zürich (specifically, Jan Novák and Marios Papas); I think this entire project has been a huge shining example of the value and importance of having a dedicated blue-sky research division. Every explosion and cloud and dust plume and every bit of fog and atmospherics you see in Ralf Breaks in the Internet was rendered using the new volume rendering system! Interestingly, we actually found that while the new volume rendering system is much faster and much more efficient at rendering dense volumes (and especially volumes with lots of high-order scattering) compared to the old system, the new system actually has some difficulty rendering thin volumes such as mist and atmospheric fog. This isn’t be surprising, since thin volumes require better transmittance sampling over better distance sampling and null collision volume rendering is really optimized for distance sampling. We were able to work with production to come up with workarounds for this problem on Ralph Breaks the Internet, but this area is definitely a good topic for future research.

Ralph Breaks the Internet is also our first feature film to move to exclusively using brute force path-traced subsurface scattering [Chiang 2016] for all characters, as a replacement for Hyperion’s previous normalized diffusion based subsurface scattering [Burley 2015]. This feature was tested on Olaf’s Frozen Adventure in a limited capacity, but Ralph Breaks the Internet is the first time we’ve switched path-traced subsurface to being to default subsurface mode in the renderer. Matt Chiang, Peter Kutz, and Brent Burley put a lot of effort into developing new sampling techniques to reduce color noise in subsurface scattering, and also into developing a new parameterization that closely matched Hyperion’s normalized diffusion parameterization, which allowed artists to basically just flip a switch between normalized diffusion and path-traced subsurface and get a predictable, similar result. Many more details on Hyperion’s path-traced subsurface implementation are in our recent system architecture paper [Burley 2018]. In addition to making characters we already know, such as Ralph and Vanellope, look better and more detailed, path-traced subsurface scattering also proved critical to hitting the required looks for new characters, such as the slug-like Double Dan character.

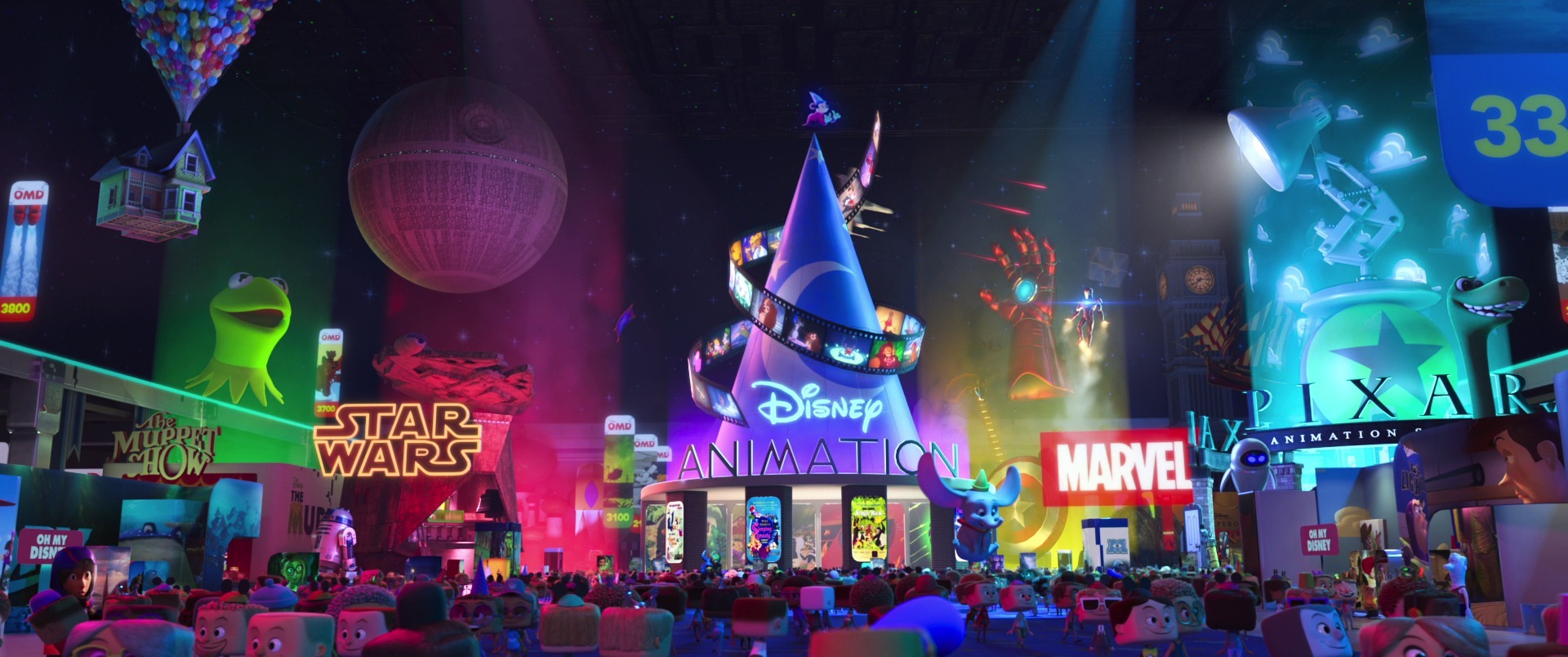

When Ralph and Vanellope first enter the world of the internet, there are several establishing shots showing vast vistas of the enormous infinite metropolis that the film depicts the internet as. Early in production, some render tests of the internet metropolis proved to be extremely challenging due to the sheer amount of geometry in the scene. Although instancing was used extensively, the way the scenes had to be built in our production pipeline meant that Hyperion wasn’t able to leverage the instancing in the scene as efficiently as we would have liked. Additionally, the way the instance groups were structured made traversal in Hyperion less ideal than it could have been. After encountering smaller-scale versions of the same problems on Moana, Peter Kutz and I had arrived at an idea that we called “multiple entry points”, which basically lets Hyperion blur the lines between top and bottom level BVHs in a two-level BVH structure. By inserting mid-level nodes from bottom level BVHs in to the top-level BVH, Hyperion can produce a much more efficient top-level BVH, dramatically accelerating rendering of large instance groups and other difficult-to-split pieces of large geometry, such as groundplanes. This idea is very similar to BVH rebraiding [Benthin et al. 2017], but we arrived at our approach independently before the publication of BVH rebraiding. After initial testing on Olaf’s Frozen Adventure proved promising, we enabled multiple entry points by default for the entirety of Ralph Breaks the Internet. Additionally, Dan Teece developed a powerful automatic geometry de-duplication system, which allows Hyperion to reclaim large amounts of memory in cases where multiple instance groups are authored with separate copies of the same master geometry. Greg Nichols and I also developed a new multithreading strategy for handling Hyperion’s ultra-wide batched ray traversal, which significantly improved Hyperion’s multithreaded scalability during traversal to near-linear scaling with number of cores. All of these geometry and traversal improvements collectively meant that by the main production push for the show, render times for the large internet vista shots had dropped from being by far the highest in the show to being indistinguishable from any other normal shot. These improvements also proved to be timely, since the internet set was just the beginning of massive-scale geometry and instancing on Ralph Breaks the Internet; solving the render efficiency problems for the internet set also made other large-scale instancing sequences, such as the Ralphzilla battle [Byun et al. 2019] at the end of the film and the massive crowds [Richards et al. 2019] in the internet, easier to render.

Another major advancement we made on Ralph Breaks the Internet, in collaboration with Disney Research Zürich and our sister studio Pixar Animation Studios, is a new machine-learning based denoiser. To the best of my knowledge, Disney Animation was one of the first studios with a successful widescale deployment of a production denoiser on Big Hero 6. The Hyperion denoiser used from Big Hero 6 through Olaf’s Frozen Adventure is a hand-tuned denoiser based on and influenced by [Li et al. 2012] and [Rousselle et al. 2012], and has since been adopted by the Renderman team as the production denoiser that ships with Renderman today. Midway through production on Ralph Breaks the Internet, David Adler from the Hyperion team in collaboration with Fabrice Rousselle, Jan Novák, Gerhard Röthilin, and others from Disney Research Zürich were able to deploy a new, next-generation machine-learning based denoiser [Vogels et al. 2018] Developed primarily by Disney Research Zürich, the new machine-learning denoiser allowed us to cut render times by up to 75% in some cases. This example is yet another case of basic scientific research at Disney Research leading to unexpected but enormous benefits to production in all of the wider Walt Disney Company’s various animation studios!

In addition to everything above, many more smaller improvements were made in all areas of Hyperion for Ralph Breaks the Internet. Dan Teece developed a really cool “edge” shader module, which was used to create all of the silhouette edge glows in the internet world, and Dan also worked closely with FX artists to develop render-side support for various fracture and destruction workflows [Harrower et al. 2018]. Brent Burley developed several improvements to Hyperion’s depth of field support, including a realistic cat’s eye bokeh effect. Finally, as always, the production of Ralph Breaks the Internet has inspired many more future improvements to Hyperion that I can’t write about yet, since they haven’t been published yet.

The original Wreck-It Ralph is one of my favorite modern Disney movies, and I think Ralph Breaks the Internet more than lives up to the original. The film is smart and hilarious while maintaining the depth that made the first Wreck-It Ralph so good. Ralph and Vanellope are just as lovable as before and grow further as characters, and all of the new characters are really awesome (Shank and Yesss and the film’s take on the Disney princesses are particular favorites of mine). More importantly for a rendering blog though, the film is also just gorgeous to look at. With every film, the whole studio takes pride in pushing the envelope even further in terms of artistry, craftsmanship, and sheer visual beauty. The number of environments and settings in Ralph Breaks the Internet is enormous and highly varied; the internet is depicted as a massive city that pushed the limits on how much visual complexity we can render (and from our previous three feature films, we can already render an unbelievable amount!), old locations from the first Wreck-It Ralph are revisited with exponentially more visual detail and richness than before, and there’s even a full on musical number with theatrical lighting somewhere in there!

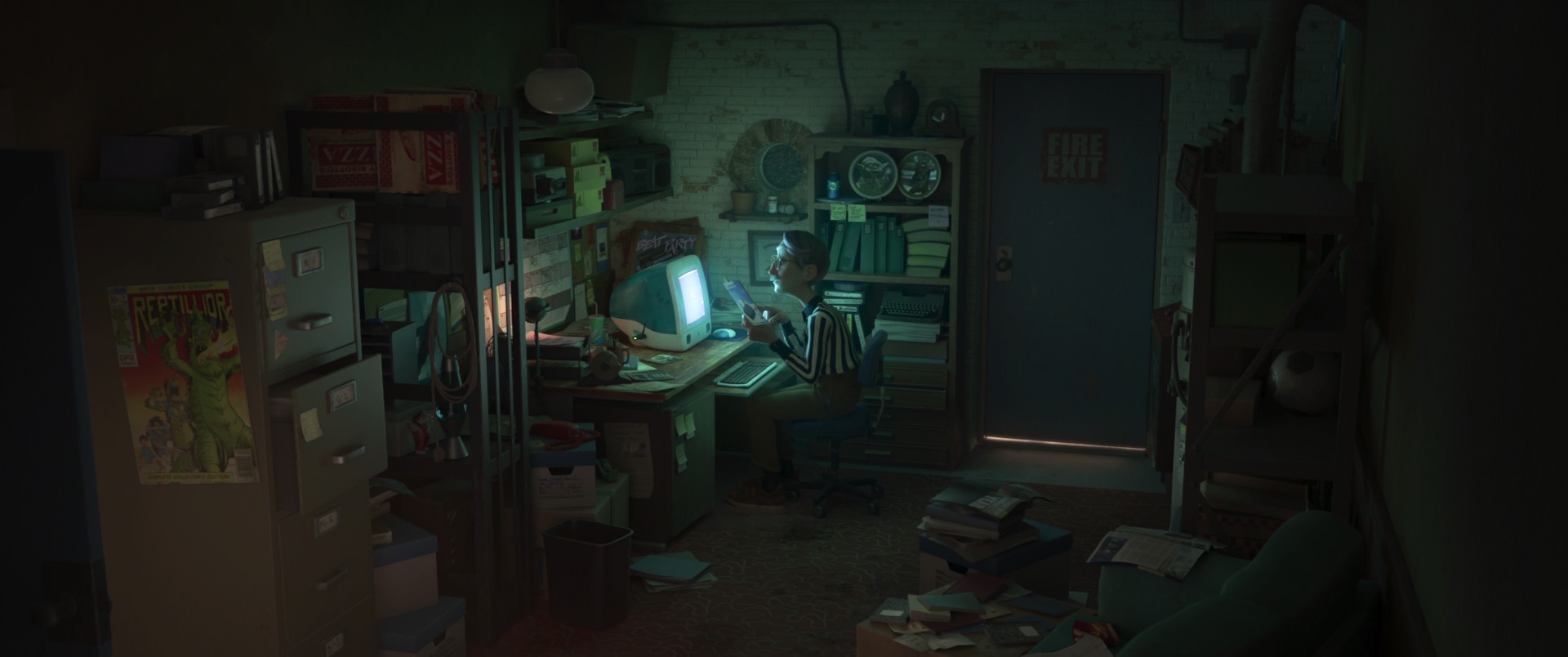

Below are some stills from the movie, in no particular order, 100% rendered using Hyperion. If you want to see more, or if you just want to see a really great movie, go see Ralph Breaks the Internet on the biggest screen you can find! There are a TON of easter eggs in the film to look out for, and I highly recommend sticking around after the credits for this one.

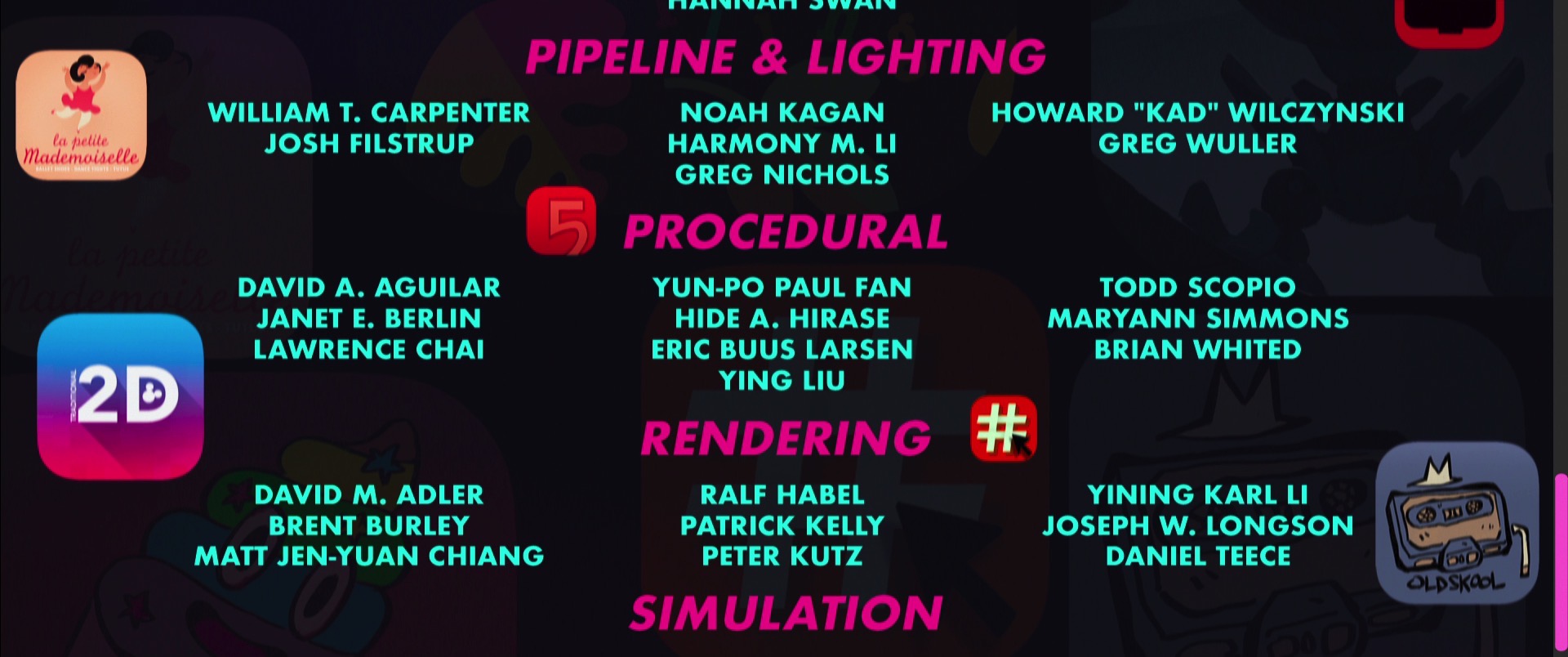

Here is the part of the credits with Disney Animation’s rendering team! Also, Ralph Breaks the Internet was my wife Harmony Li’s first credit at Disney Animation (she previously was at Pixar)! This frame is kindly provided by Disney. Every person you see in the credits worked really hard to make Ralph Breaks the Internet an amazing film!

All images in this post are courtesy of and the property of Walt Disney Animation Studios.

References

Carsten Benthin, Sven Woop, Ingo Wald, and Attila T. Áfra. 2017. Improved Two-Level BVHs using Partial Re-Braiding. In Proc. of High Performance Graphics (HPG 2017). Article 7.

Brent Burley. 2015. Extending the Disney BRDF to a BSDF with Integrated Subsurface Scattering. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2015 Course Notes: Physically Based Shading in Theory and Practice.

Brent Burley, David Adler, Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang, Hank Driskill, Ralf Habel, Patrick Kelly, Peter Kutz, Yining Karl Li, and Daniel Teece. 2018. The Design and Evolution of Disney’s Hyperion Renderer. ACM Transactions on Graphics 37, 3 (Jul. 2018), Article 33.

Dong Joo Byun, Alberto Luceño Ros, Alexander Moaveni, Marc Bryant, Joyce Le Tong, and Moe El-Ali. 2019. Creating Ralphzilla: Moshpit, Skeleton Library and Automation Framework. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2019 Talks. Article 66.

Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang, Peter Kutz, and Brent Burley. 2016. Practical and Controllable Subsurface Scattering for Production Path Tracing. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2016 Talks. Article 49.

Julian Fong, Magnus Wrenninge, Christopher Kulla, and Ralf Habel. 2017. Production Volume Rendering. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2017 Courses. Article 2.

Will Harrower, Pete Kyme, Ferdi Scheepers, Michael Rice, Marie Tollec, and Alex Moaveni. 2018. SimpleBullet: Collaborating on a Modular Destruction Toolkit. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2018 Talks. Article 79.

Peter Kutz, Ralf Habel, Yining Karl Li, and Jan Novák. 2017. Spectral and Decomposition Tracking for Rendering Heterogeneous Volumes. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH) 36, 4 (Aug. 2017), Article 111.

Tzu-Mao Li, Yu-Ting Wu, and Yung-Yu Chiang. 2012. SURE-based Optimization for Adaptive Sampling and Reconstruction. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH Asia) 31, 6 (Nov. 2012), Article 194.

Jan Novák, Andrew Selle and Wojciech Jarosz. 2014. Residual Ratio Tracking for Estimating Attenuation in Participating Media. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH Asia) 33, 6 (Nov. 2014), Article 179.

Josh Richards, Joyce Le Tong, Moe El-Ali, and Tuan Nguyen. 2019. Optimizing Large Scale Crowds in Ralph Breaks the Internet. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2019 Talks. Article 65.

Fabrice Rousselle, Marco Manzi, and Matthias Zwicker. 2013. Robust Denoising using Feature and Color Information. Computer Graphics Forum (Proc. of Eurographics Symposium on Rendering) 32, 7 (Jun. 2013), 121-130.

Thijs Vogels, Fabrice Rousselle, Brian McWilliams, Gerhard Röthlin, Alex Harvill, David Adler, Mark Meyer, and Jan Novák. 2018. Denoising with Kernel Prediction and Asymmetric Loss Functions. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH) 37, 4 (Aug. 2018), Article 124.