SIGGRAPH 2022 Talk- "Encanto" - Let's Talk About Bruno's Visions

This year at SIGGRAPH 2022, Corey Butler, Brent Burley, Wei-Feng Wayne Huang, Benjamin Huang, and I have a talk that presents the technical and artistic challenges and solutions that went into creating the holographic look for Bruno’s visions in Encanto. In Encanto, Bruno is a character who has a magical gift of being able to see into the future, and the visions he sees of the future get crystalized into a sort of glassy emerald tablet with the vision embedded in the glassy surface with a holographic effect. Coming up with this unique look and an efficient and robust authoring workflow required a tight collaboration between visual development, lookdev, lighting, and the Hyperion rendering team to develop a custom solution in Disney’s Hyperion Renderer. On the artist side, Corey was the main lighter and Benjamin was the main lookdev artist for this project, while on the rendering team side, Wayne and I worked closely together to develop a series of prototype shaders that were instrumental in defining how the effect should look and then Brent came up with the implementation approach for the final production version of the shader. This project was a lot of fun to be a part of and in my opinion really demonstrates the benefits of having an in-house rendering team that works closely with and embedded within a production context.

Here is the paper abstract:

In Walt Disney Animation Studios’ “Encanto”, Mirabel discovers the remnants of her Uncle Bruno’s mysterious visions of the future. Developing the look and lighting for the emerald shards required close collaboration between our Visual Development, Look Development, Lighting, and Technology departments to create a holographic effect. With an innovative new teleporting holographic shader, we were able to bring a unique and unusual effect to the screen.

The paper and related materials can be found at:

When Corey first came to the rendering team with the request for a more efficient way to create the hologram effect that lighting had prototyped using camera mapping, our initial instinct actually wasn’t to develop a new shader at all. Hyperion has an existing “hologram” shader that was developed for use on Big Hero 6 [Joseph et al. 2014], and our initial instinct was to tell Corey that they should use the hologram shader. The way the Big Hero 6 era hologram shader works is: upon hitting a surface that has the hologram shader applied, the ray is moved into a virtual space containing a bunch of imaginary parallel planes, with each plane textured with a 2D slice of a 3D interior. In some ways the hologram shader can be thought of as raymarching through a sparse volumetric representation of a 3D interior, but the sparse volumetric interior really is just a stack of 2D slices. This technique works really well for things like building interiors seen through glass windows. However, our artists… really dislike using the hologram shader, to put things lightly. The problem with the hologram shader is that setting up the 2D slices that are inputs to the shader is an incredibly annoying and difficult process, and since the 2D slice baker has to be run as an offline process before the shader can be authored and rendered, making changes and iterating on the contents of the hologram shader is a slow process. Furthermore, if the inside of the hologram shader has to be animated, the slice baker needs to be run for every frame. We were told in no uncertain terms that the hologram shader was likely more work to set up and iterate on than the already painful manual camera mapping approach that the artists had prototyped the effect with. This request also came to us fairly late in Encanto’s production schedule, so easy setup and fast iteration times along with an extremely accelerated development timeline were hard requirements for whatever approach we took.

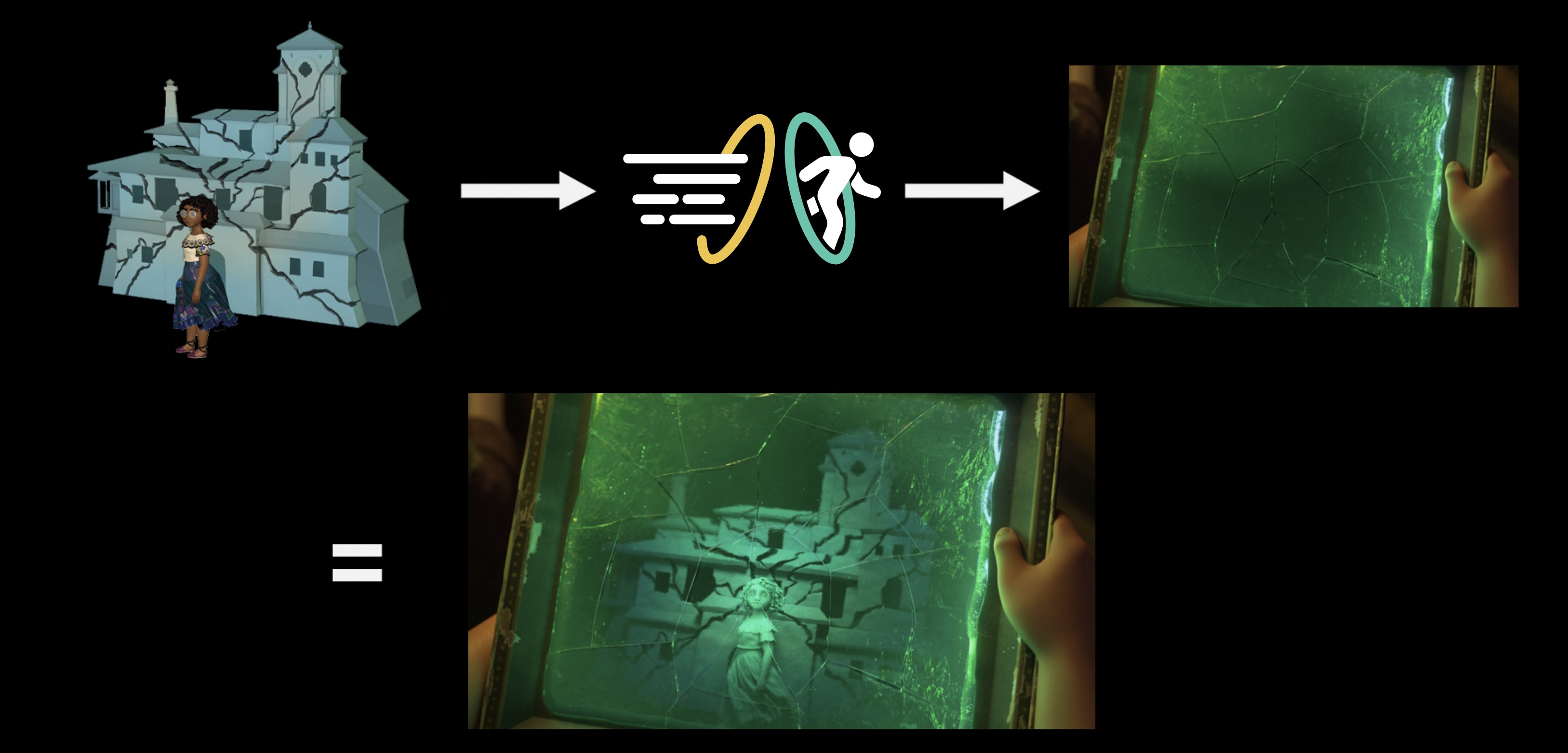

Upon receiving this feedback, Wayne and I set out to prototype a version of the teleportation shader that Pixar came up with for the portals in Incredibles 2 [Coleman et al. 2014]. This process was a lot of fun; Wayne and I spent a few days rapidly iterating on several different ideas for both how to implement ray teleportation in Hyperion and on how the artist workflow and interface for this new teleportation system should work. At the same time that we were prototyping, we started giving test builds of our latest prototypes to Corey to try out, which produced a feedback loop where Corey would use our prototypes to further iterate on how the final effect would look and go back and forth with the movie’s production designer and we would use Corey’s feedback to further improve the prototype. One example of where our prototype directly informed the final look was in how the prophecies fade away towards the edges of the emerald tablet- Wayne and I threw in a feature where artists could use a map to paint in the ratio of teleportation effect versus normal surface BSDF that would be applied at each surface point, and this feature wound up driving the faded edges.

The key thing that made our new approach work better than the old hologram shader was in simplicity of setup. Instead of having to run a pre-bake process and then wire up a whole bunch of texture slices into the renderer, our new approach was designed so that all an artist had to do was set up the 3D geometry that they wanted to put inside of the hologram in a target space hidden somewhere in the overall scene (typically below the ground plane in a black box or something), and then select the geometry in the main scene that they wanted to act as the “entrance” portal, select the geometry in the target space that they wanted to act as the “exit” portal, and link the two using the teleportation shader. The renderer then did all of the rest of the work of figuring out how each point on the entrance portal corresponded to the surface of the exit portal, how transforms needed to be calculated, and so on and so forth. Multiple portal pairs could be set up in a single scene too, and the contents of a world seen through a portal could contain more portals, all of which was important because in the movie, Mirabel initially finds Bruno’s prophecy broken into shards, which had to be set up as a separate entrance portal per shard all into the same interior world. Since all of this just piggy-backed off of the normal way artists set up scenes, things like animation just worked out-of-the-box with no additional code or effort.

The last piece of the puzzle fell into place when Wayne and I discussed our progress with Brent. One of the big remaining challenges for us was that tracking correspondences between entrance and exit geometry and transforms was prone to easy breakage if input geometry wasn’t set up exactly the way we expected. At the time Brent was working on a new fracture-aware tessellation system for subdivision surfaces in Hyperion [Burley and Rodriguez 2022], and Brent quickly realized that the approach we were using for figuring out the transform from the entrance to the exit portal could be replaced with something he had already developed for the fracture-aware tessellation system. Specifically, the fracture-aware tessellation system has to be able to calculate correspondences between undeformed unfractured reference points and corresponding points in a deformed fractured fragment space; this is done using a best-fit process to find orthonormal transforms [Horn et al. 1998]. Brent realized that the problem we were trying to solve was actually the same problem he that he had already solved in the fracture system, so he took our latest prototype and reworked the internals to use the same best-fit orthonormal transform solution as in the fracturing system. With Brent’s improvements, we arrived at the final production version of the teleportation shader used on Encanto.

Going from the start of brainstorming and prototyping to delivering the final production version of the shader took us a little over a week, which anyone who has worked in an animation/VFX production setting before will know is very fast for a large new rendering feature. Working tightly with Corey and Benjamin to simultaneously iterate on the art and the software and inform each other was key to this project’s fast development time and key to achieving an amazing looking effect in the film. At Disney Animation, we have a mantra that goes “art challenges technology and technology inspires the art”- this project was a case that exemplifies how we carry out that mantra in real-world filmmaking and demonstrates the amazing results that come out of such a process. Bruno’s visions in Encanto are every bit a case where the artistic vision challenged us to develop new technology, and the process of iterating on the new technology between engineers and artists in turn informed the final artwork that made it into the movie; for me, projects like these are one of the things that makes Disney Animation such a fun and amazing place to be.

References

Brent Burley, David Adler, Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang, Hank Driskill, Ralf Habel, Patrick Kelly, Peter Kutz, Yining Karl Li, and Daniel Teece. 2018. The Design and Evolution of Disney’s Hyperion Renderer. ACM Transactions on Graphics 37, 3 (Jul. 2018), Article 33.

Brent Burley and Francisco Rodriguez. 2022. Fracture-Aware Tessellation of Subdivision Surfaces. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2022 Talks. Article 10.

Patrick Coleman, Darwyn Peachey, Tom Nettleship, Ryusuke Villemin, and Tobin Jones. 2018. Into the Voyd: Teleportation of Light Transport in Incredibles 2. In Proc. of Digital Production Symposium (DigiPro 2018). Article 12.

Berthold K. P. Horn, Hugh M. Hilden, and Shahriar Negahdaripour. 1988. Close-Form Solution of Absolute Orientation using Orthonormal Matrices. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 5, 7 (Jul. 1988), 1127–1135.

Norman Moses Joseph, Brett Achorn, Sean D. Jenkins, and Hank Driskill. Visualizing Building Interiors Using Virtual Windows. In ACM SIGGRAPH Asia 2014 Technical Briefs. Article 18.