Scandinavian Room Scene

Almost three years ago, I rendered a small room interior scene to test an indoor, interior illumination scenario. Since then, a lot has changed in Takua, so I thought I’d revisit an interior illumination test with a much more complex, difficult scene. I don’t have much time to model stuff anymore these days, so instead I bought Evermotion’s Archinteriors Volume 48 collection, which is labeled as Scandinavian interior room scenes (I don’t know what’s particularly Scandinavian about these scenes, but that’s what the label said) and ported one of the scenes to Takua’s scene format. Instead of simply porting the scene as-is, I modified and added various things in the scene to make it feel a bit more customized. See if you can spot what they are:

I had a lot of fun adding all of my customizations! I brought over some props from the old complex room scene, such as the purple flowers and vase, a few books, and Utah teapot tray, and also added a few new fun models, such as the MacBook Pro in the back and the copy of Physically Based Rendering 3rd Edition in the foreground. The black and white photos on the wall are crops of my Minecraft renders, and some of the books against the back wall have fun custom covers and titles. Even all of the elements that came with the original scene are re-shaded. The original scene came with Vray’s standard VrayMtl as the shader for everything; Takua’s base shader parameterization draws some influence from Vray, but also draws from the Disney Bsdf and Arnold’s AlShader and as a result has a parameterization that is sufficiently different that I wound up just re-shading everything instead of trying to write some conversion tool. For the most part I was able to re-use the textures that came with the scene to drive various shader parameters. The skydome is from the noncommercial version of VizPeople’s HDRi v1 collection.

Speaking of the skydome… the main source of illumination in this scene comes from the sun in the skydome, which presented a huge challenge for efficient light sampling. Takua has had domelight/environment map importance sampling using CDF inversion sampling for a long time now, which helps a lot, but the indoor nature of this scene still made sampling the sun difficult. Sampling the sun in an outdoor scene is fairly efficient since most rays will actually reach the sun, but in indoor scenes, importance sampling the sun becomes inefficient without taking occlusion into account since only rays that actually make it outdoors through windows can reach the sun. The best known method currently for handling domelight importance sampling through windows in an indoor scene is Portal Masked Environment Map Sampling (PMEMS) by Bitterli et al. I haven’t actually implemented PMEMS yet though, so the renders in this post all wound up requiring a huge number of samples per pixel to render; I intend on implementing PMEMS at some point in the near future.

Apart from the skydome, this scene also contains several other practical light sources, such as the lamp’s bulb, the MacBook Pro’s screen, and the MacBook Pro’s glowing Apple logo on the back of the screen (which isn’t even visible to camera, but is still enabled since it provides a tiny amount of light against the back wall!). In addition to choosing where on a single light to sample, choosing which light to sample is also an extremely important and difficult problem. Until this rendering this scene, I hadn’t really put any effort into efficiently selecting which light to sample. Most of my focus has been on the integration part of light transport, so Takua’s light selection has just been uniform random selection. Uniform random selection is terrible for scenes that contain multiple lights with highly varying emission between different lights, which is absolutely the case for this scene. Like any other importance sampling problem, the ideal solution is to send rays towards lights with a probability proportional to the amount of illumination we expect each light to contribute to each ray origin point.

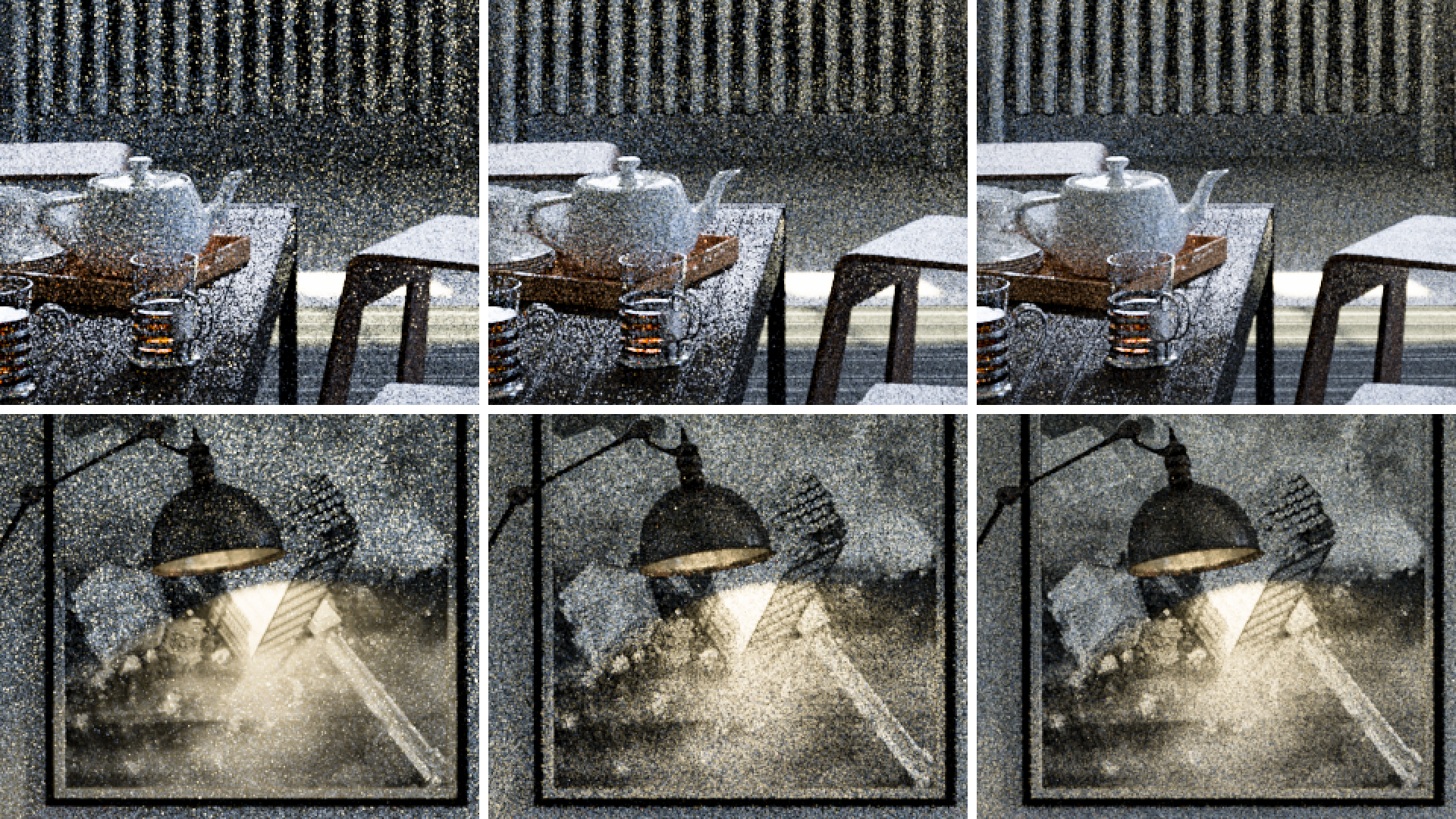

I implemented a light selection strategy where the probability of selecting each light is weighted by the total emitted power of each light; essentially this boils down to estimating the total emitted power of each light according to the light’s surface texture and emission function, building a CDF across all of the lights using the total emission estimates, and then using standard CDF inversion sampling to pick lights. This strategy works significantly better than uniform random selection and made a huge difference in render speed for this scene, as seen in Figures 2 through 4. Figure 2 uses uniform random light selection with 128 spp; note how the area lit by the wall-mounted lamp is well sampled, but the image overall is really noisy. Figure 3 uses power-weighted light selection with the same spp as Figure 2; the lamp area is more noisy than in Figure 2, but the render is less noisy overall. Notably, Figure 3 also took a third of the time compared to Figure 2 for the same sample count; this is because in this scene, sending rays towards the lamp is significantly more expensive due to heavier geometry than sending rays towards the sun, even when rays towards the sun get occluded by the walls. Figure 4 uses power-weighted light selection again, but is equal-time to Figure 2 instead of equal-spp; note the significant noise reduction:

However, power-weighted light selection still is not even close to being the most optimal technique possible; this technique completely ignores occlusion and distance, which are extremely important. Unfortunately, because occlusion and distance to each light varies for each point in space, creating a light selection strategy that takes occlusion and distance into account is extremely difficult and is a subject of continued research in the field. In Hyperion, we use a cache point system, which we described on page 97 of our SIGGRAPH 2017 Production Volume Rendering course notes. Other published research on the topic includes Practical Path Guiding for Efficient Light-Transport Simulation by Muller et al, On-line Learning of Parametric Mixture Models for Light Transport Simulation by Vorba et al, Product Importance Sampling for Light Transport Path Guiding by Herholz et al, Learning Light Transport the Reinforced Way by Dahm et al, and more. At some point in the future I’ll revisit this topic.

For a long time now, Takua has also had a simple interactive mode where the camera can be moved around in a non-shaded/non-lit view; I used this mode to interactively scout out some interesting and fun camera angles for some more renders. Being able to interactively scout in the same renderer used to final rendering is an extremely powerful tool; instead of guessing at depth of field settings and such, I was able to directly set and preview depth of field with immediate feedback. Unfortunately some of the renders below are noisier than I would like, due to the previously mentioned light sampling difficulties. All of the following images are rendered using Takua a0.8 with VCM:

Beyond difficult light sampling, generally complex and difficult light transport with lots of subtle caustics also wound up presenting major challenges in this scene. For example, note the subtle caustics on the wall in the upper right hand part of Figure 10; those caustics are actually visibly not fully converged, even though the sample count across Figure 10 was in the thousands of spp! I intentionally did not use adaptive sampling in any of these renders; instead, I wanted to experiment with a common technique used in a lot of modern production renderers for noise reduction: in-render firefly clamping. My adaptive sampler is already capable of detecting firefly pixels and driving more samples at fireflies in the hopes of accelerating variance reduction on firefly pixels, but firefly clamping is a much more crude, biased, but nonetheless effective technique. The idea is to detect on each pixel spp if a returned sample is an outlier relative to all of the previously accumulated samples, and discard or clamp the sample if it in fact is an outlier. Picking what threshold to use for outlier detection is a very manual process; even Arnold provides a tuning max-value parameter for firefly clamping.

I wanted to be able to directly compare the render with and without firefly clamping, so I implemented firefly clamping on top of Takua’s AOV system. When enabled, firefly clamping mode produces two images for a single render: one output with firefly clamping enabled, and one with clamping disabled. I tried re-rendering Figure 10 using unidirectional pathtracing and a relatively low spp count to produce as many fireflies as I could, for a clearer comparison. For this test, I set the firefly threshold to be samples that are at least 250 times brighter than the estimated pixel value up to that sample.

Note how Figure 13 appears to be completely firefly-free compared to Figure 12, and how Figure 13 doesn’t have visible caustic noise on the walls compared to Figure 10. However, notice how Figure 13 is also missing significant illumination in some areas, such as in the corner of the walls near the floor behind the wooden step ladder, or in the deepest parts of the purple flower bunch. Finding a threshold that eliminates all fireflies without loosing significant illumination in other areas is very difficult or, in some cases, impossible since some of these types of light transport essentially manifest as firefly-like high energy samples that only smooth out over time. For the final renders in Figure 1 and Figures 6 through 11, I wound up not actually using any firefly clamping. While biased noise-reduction techniques are a necessary evil in actual production, I expect that I’ll try to avoid relying on firefly clamping in the vast majority of what I do with Takua, since Takua is meant to just be a brute-force, hobby kind of thing anyway.