New PIC/FLIP Simulator

Over the past month or so, I’ve been writing a brand new fluid simulator from scratch. It started as a project for a course/seminar type thing I’ve been taking with Professor Doug James, but I’ve been working on since the course ended for fun. I wanted to try our implementing the PIC/FLIP method from Zhu and Bridson; in industry, PIC/FLIP has more or less become the de fact standard method for fluid simulation. Houdini and Naiad both use PIC/FLIP implementations as their core fluid solvers, and I’m aware that Double Negative’s in-house simulator is also a PIC/FLIP implementation.

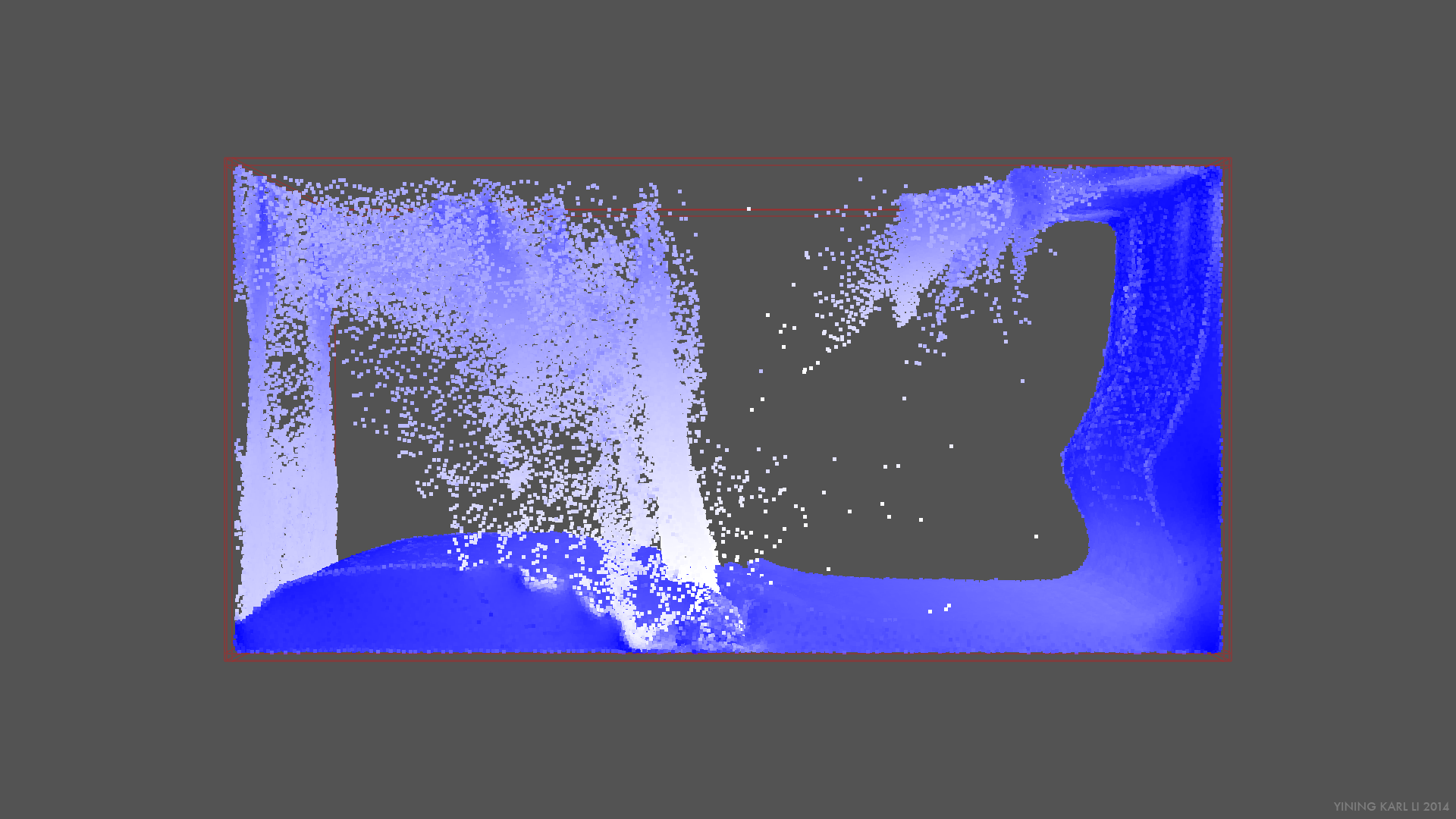

I’ve named my simulator “Ariel”, since I like Disney movies and the name seemed appropriate for a project related to water. Here’s what a “dambreak” type simulation looks like:

That “dambreak” test was run with approximately a million particles, with a 128x64x64 grid for the projection step.

PIC/FLIP stands for Particle-In-Cell/Fluid-Implicit Particles. PIC and FLIP are actually two separate methods that each have certain shortcomings, but when used together in a weighted sum, produces a very stable fluid solver (my own solver uses approximately a 90% FLIP to 10% PIC ratio). PIC/FLIP is similar to SPH in that it’s fundamentally a particle based method, but instead of attempting to use external forces to maintain fluid volume, PIC/FLIP splats particle velocities onto a grid, calculates a velocity field using a projection step, and then copies the new velocities back onto the particles for each step. This difference means PIC/FLIP doesn’t suffer from the volume conservation problems SPH has. In this sense, PIC/FLIP can almost be thought of as a hybridization of SPH and semi-Lagrangian level-set based methods. From this point forward, I’ll refer to the method as just FLIP for simplicity, even though it’s actually PIC/FLIP.

I also wanted to experiment with OpenVDB, so I built my FLIP solver on top of OpenVDB. OpenVDB is a sparse volumetric data structure library open sourced by Dreamworks Animation, and now integrated into a whole bunch of systems such as Houdini, Arnold, and Renderman. I played with it two years ago during my summer at Dreamworks, but didn’t really get too much experience with it, so I figured this would be a good opportunity to give it a more detailed look.

My simulator uses OpenVDB’s mesh-to-levelset toolkit for constructing the initial fluid volume and solid obstacles, meaning any OBJ meshes can be used to building the starting state of the simulator. For the actual simulation grid, things get a little bit more complicated; I initially started with using OpenVDB for storing the grid for the projection step with the idea that storing the projection grid sparsely should allow for scaling the simulator to really really large scenes. However, I quickly ran into the ever present memory-speed tradeoff of computer science. I found that while the memory footprint of the simulator stayed very small for large sims, it ran almost ten times slower compared to when the grid is stored using raw floats. The reason is that since OpenVDB under the hood is a B+tree, constant read/write operations against a VDB grid end up being really expensive, especially if the grid is not very sparse. The fact that VDB enforces single-threaded writes due to the need to rebalance the B+tree does not help at all. As a result, I’ve left in a switch that allows my simulator to run in either raw float of VDB mode; VDB mode allows for much larger simulations, but raw float mode allows for faster, multithreaded sims.

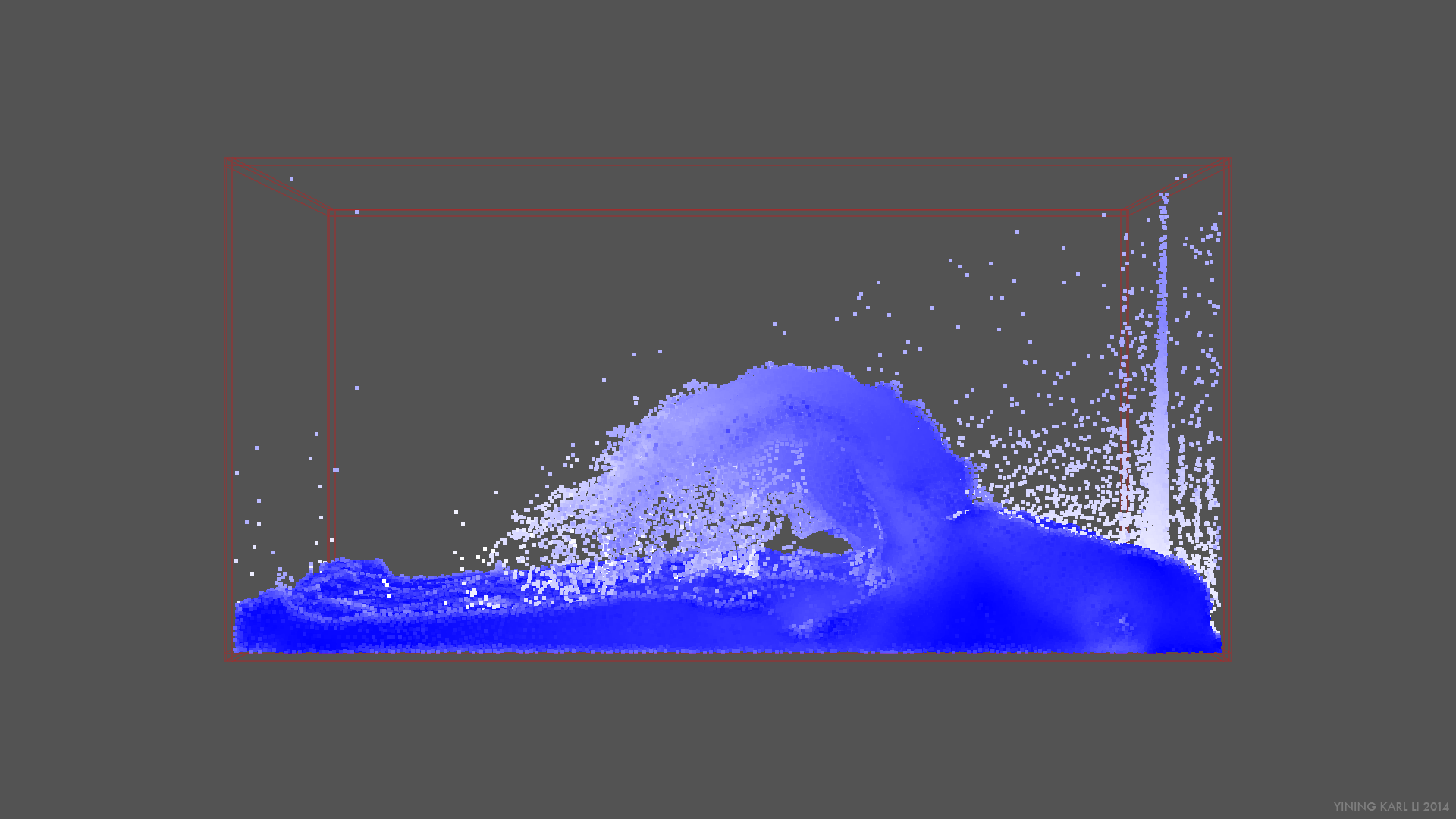

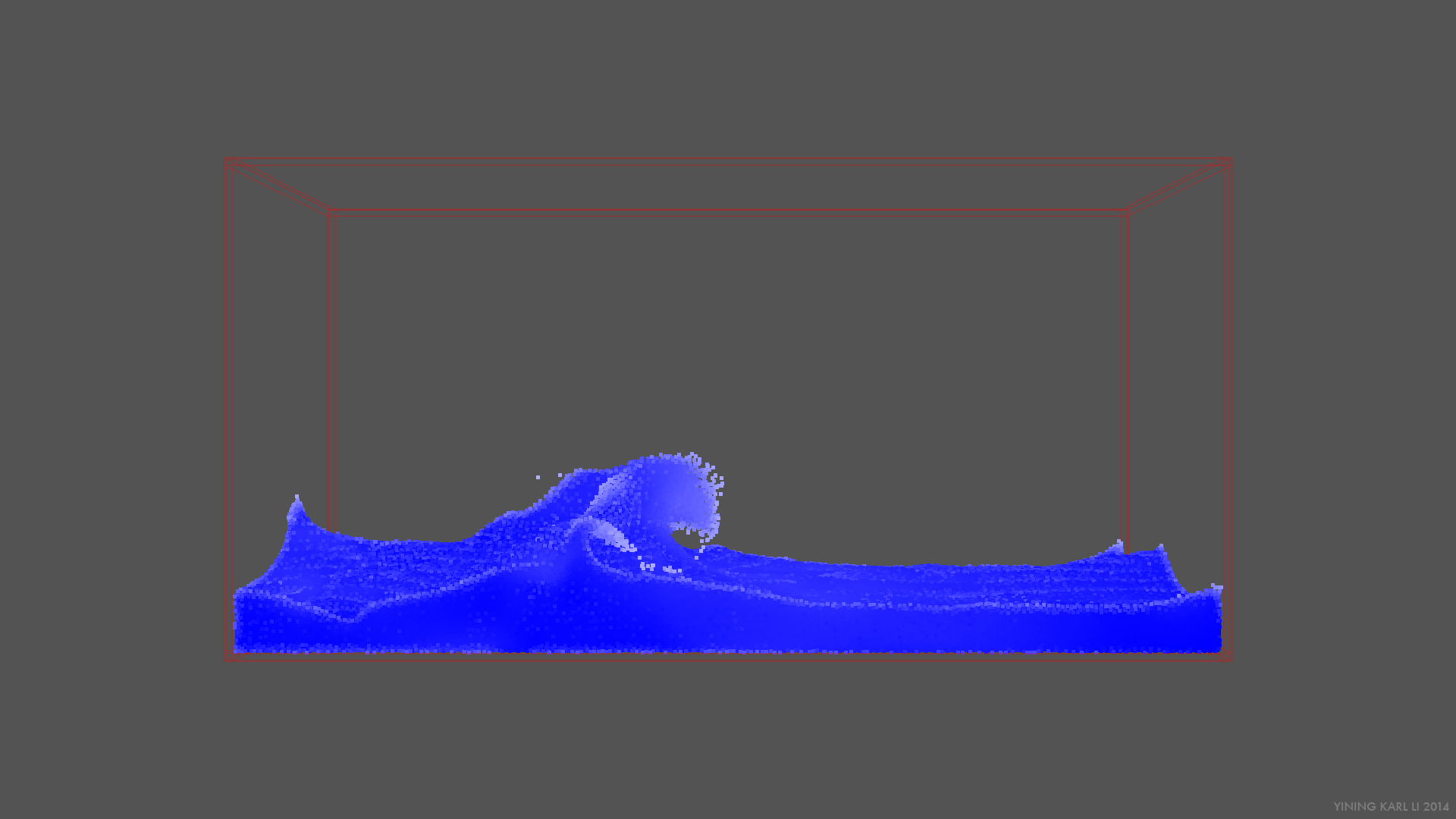

Here’s a video of another test scene, this time patterned after a “waterfall” type scenario. This test was done earlier in the development process, so it doesn’t have the wireframe outlines of the solid boundaries:

In the above videos and stills, blue indicates higher density/lower velocity, white indicate lower density/higher velocity.

Writing the core PIC/FLIP solver actually turned out to be pretty straightforward, and I’m fairly certain that my implementation is correct since it closely matches the result I get out of Houdini’s FLIP solver for a similar scene with similar parameters (although not exactly, since there’s bound to be some differences in how I handle certain details, such as slightly jittering particle positions to prevent artifacting between steps). Figuring out a good meshing and rendering pipeline turned out to be more difficult; I’ll write about that in my next post.