TAKUA/Avohkii Renderer

One question I’ve been asking myself ever since my friend Peter Kutz and I wrapped our little GPU Pathtracer experiment is “why am I writing Takua Renderer as a CPU-only renderer?” One of the biggest lessons learned from the GPU Pathtracer experiment was that GPUs can indeed provide vast quantities of compute suitable for use in pathtracing rendering. After thinking for a bit at the beginning of the summer, I’ve decided that since I’m starting my renderer from scratch and don’t have to worry about the tons of legacy that real-world big boy renderers like RenderMan have to deal with, there is no reason why I shouldn’t architect my renderer to use whatever compute power is available.

With that being said, from this point forward, I will be concurrently developing CPU and GPU based implementations of Takua Renderer. I call this new overall project TAKUA/Avohkii, mainly because Avohkii is a cool name. Within this project, I will continue developing the C++ based x86 version of Takua, which will retain the name of just Takua, and I will also work on a CUDA based GPU version, called Takua-RT, with full feature parity. I’m also planning on investigating the idea of an ARM port, but that’s an idea for later. I’m going to stick with CUDA for the GPU version now since I know CUDA better than OpenCL and since almost all of the hardware I have access to develop and test on right now is NVIDIA based (the SIG Lab runs on NVIDIA cards…), but that could change down the line. The eventual goal is to have a set of renderers that together cover as many hardware bases as possible, and can all interoperate and intercommunicate for farming purposes.

I’ve already gone ahead and finished the initial work of porting Takua Renderer to CUDA. One major lesson learned from the GPU Pathtracer experiment was that enormous CUDA kernels tend to run into a number of problems, much like massive monolithic GL shaders do. One problem in particular is that enormous kernels tend to take a long time to run and can result in the GPU driver terminating the kernel, since NVIDIA’s drivers by default assume that device threads taking longer than 2 seconds to run are hanging and cull said threads. In the GPU Pathtracer experiment, we used a giant monolithic kernel for a single ray bounce, which ran into problems as geometry count went up and subsequently intersection testing and therefore kernel execution time also increased. For Takua-RT, I’ve decided to split a single ray bounce into a sequence of micro-kernels that launch in succession. Basically, each operation is now a kernel; each intersection test is a kernel, BRDF evaluation is a kernel, etc. While I suppose I lose a bit of time in having numerous kernel launches, I am getting around the kernel time-out problem.

Another important lesson learned was that culling useless kernel launches is extremely important. I’m checking for empty threads at the end of each ray bounce and culling via string compaction for now, but this can of course be further extended to the micro-kernels for intersection testing later.

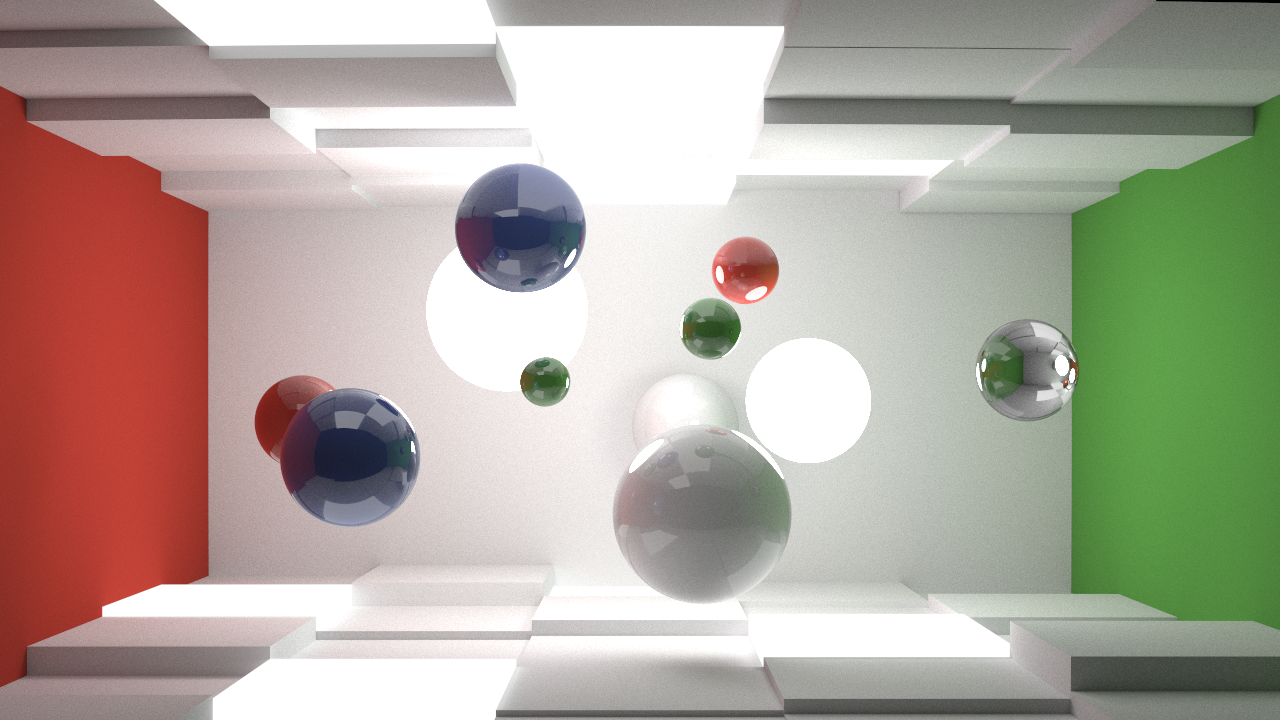

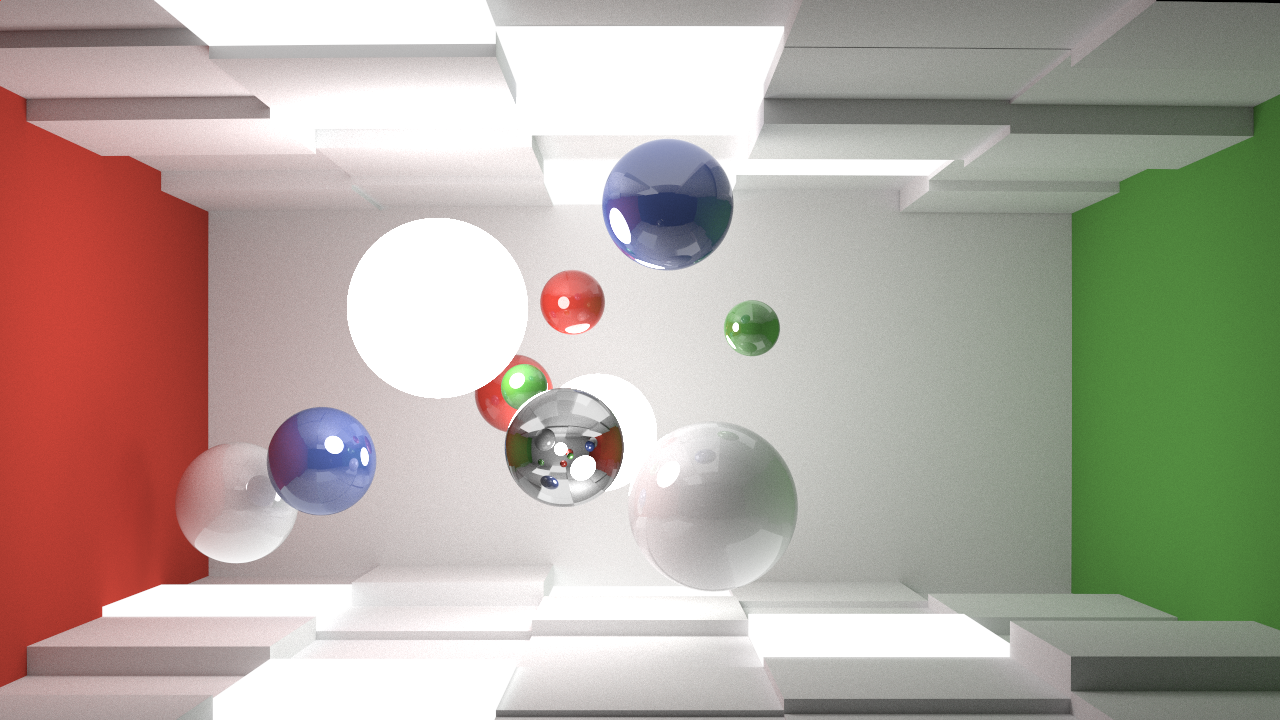

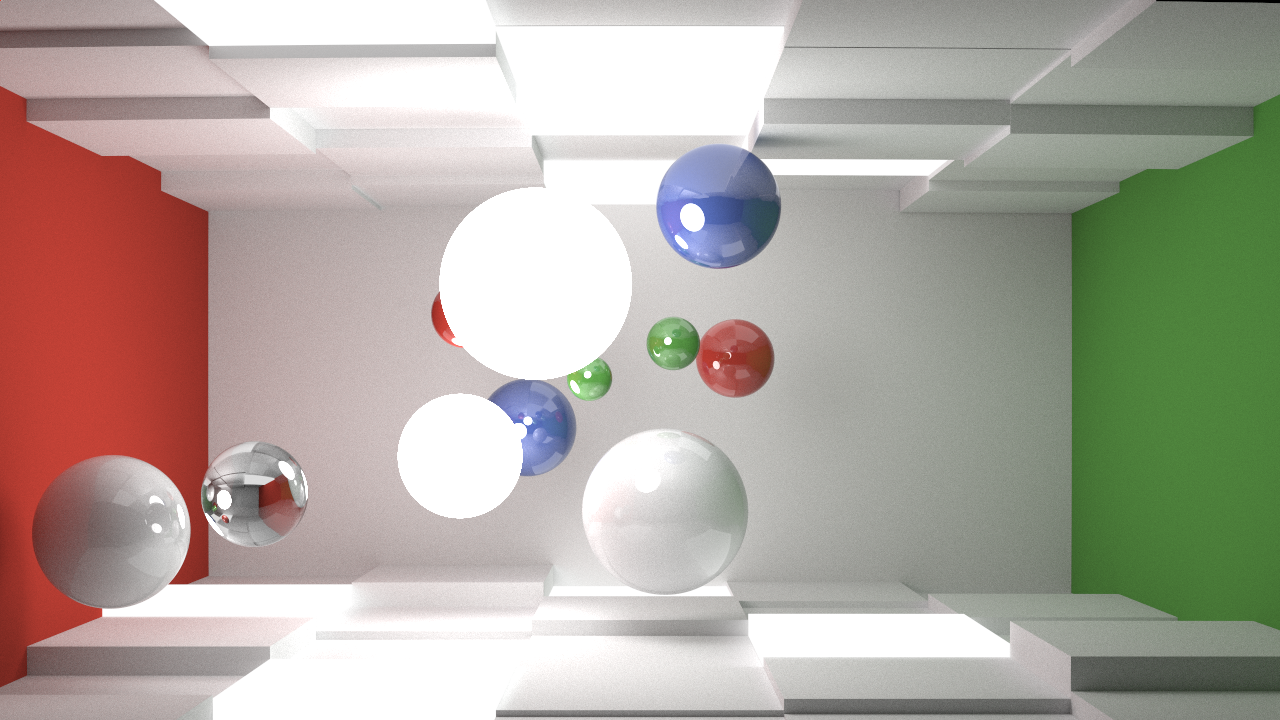

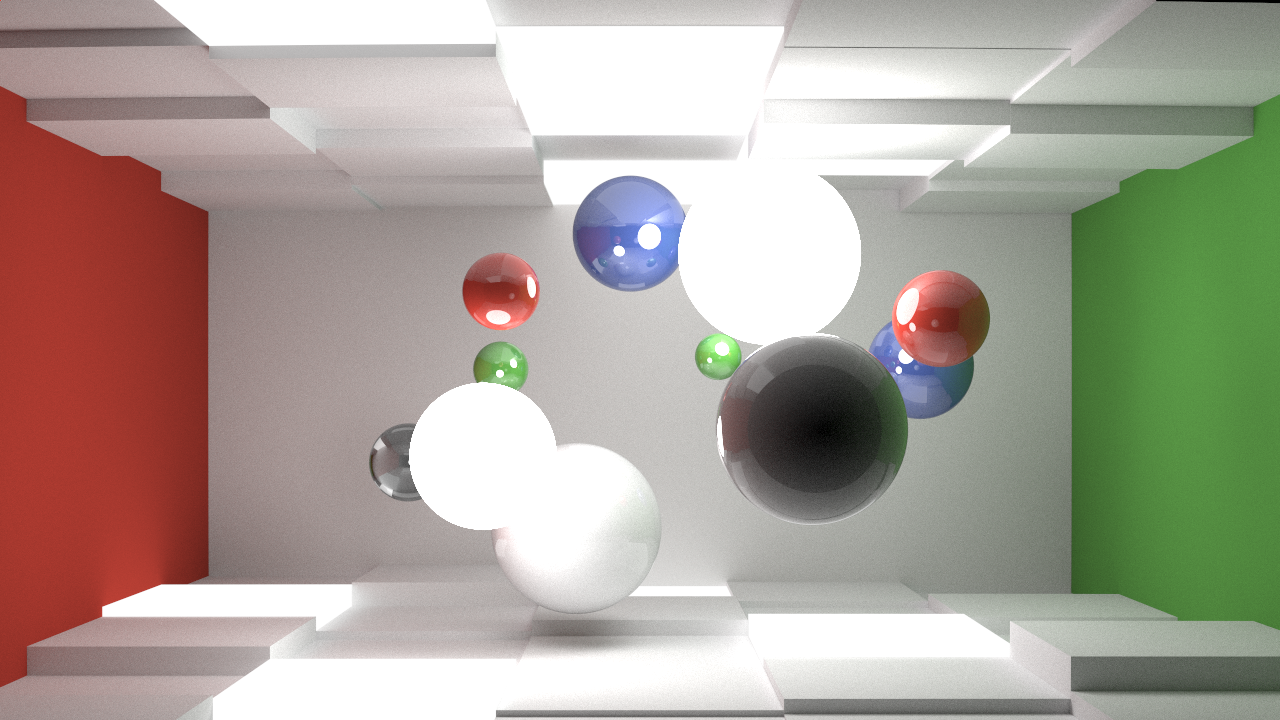

Anyhow, enough text. Takua-RT, even in its super-naive unoptimized CUDA-port state right now, is already so much faster than the CPU version that I can render frames with fairly high convergence in seconds to minutes. That means the renderer is now fast enough for use on rendering animations, such as the one at the top of this post. No post-processing whatsoever was applied, aside from my name watermark in the lower right hand corner. The following images are raw output frames from Takua-RT, this time straight from the renderer, without even watermarking:

Each of these frames represents 5000 iterations of convergence, and took about a minute to render on a NVIDIA Geforce GTX480. The flickering in the glass ball in animated version comes from having a low trace depth of 3 bounces, including for glass surfaces.