Moana

2016 is the first year ever that Walt Disney Animation Studios is releasing two CG animated films. We released Zootopia back in March, and next week, we will be releasing our newest film, Moana. I’ve spent the bulk of the last year and a half working as part of Disney’s Hyperion Renderer team on a long list of improvements and new features for Moana. Moana is the first film I have an official credit on, and I couldn’t be more excited for the world to see what we have made!

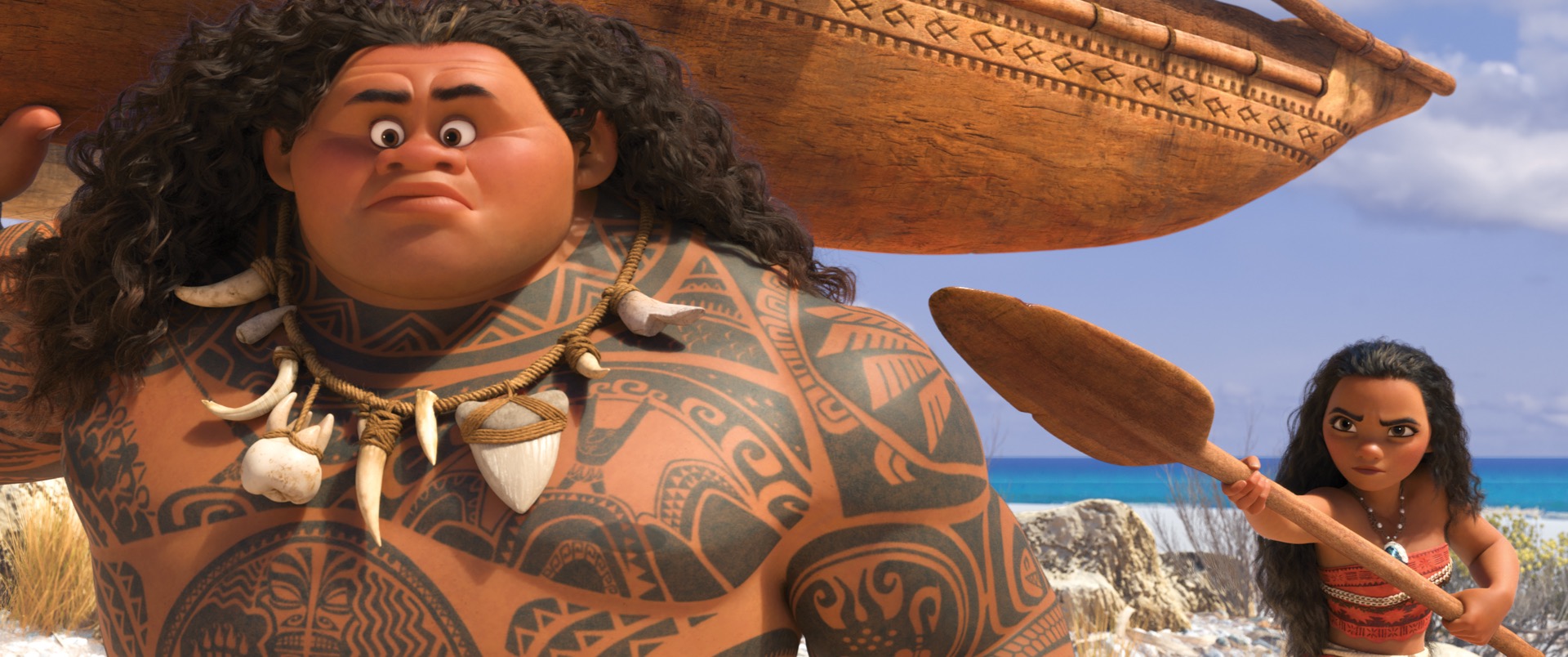

We’re all incredibly proud of Moana; the story is fantastic, the characters are fresh and deep and incredibly appealing, and the music is an instant classic. Most important for a rendering guy though, I think Moana is flat out the best looking animated film anyone has ever made. Every single department on this film really outdid themselves. The technology that we had to develop for this film was staggering; we have a whole new distributed fluid simulation package for the endless oceans in the film, we added advanced new lighting capabilities to Hyperion that have never been used in an animated film before to this extent (to the best of my knowledge), we made huge advances in our animation technology for characters such as Maui; the list goes on and on and on. Something like over 85% of the shots in this movie have significant FX work in them, which is unheard of for animated features.

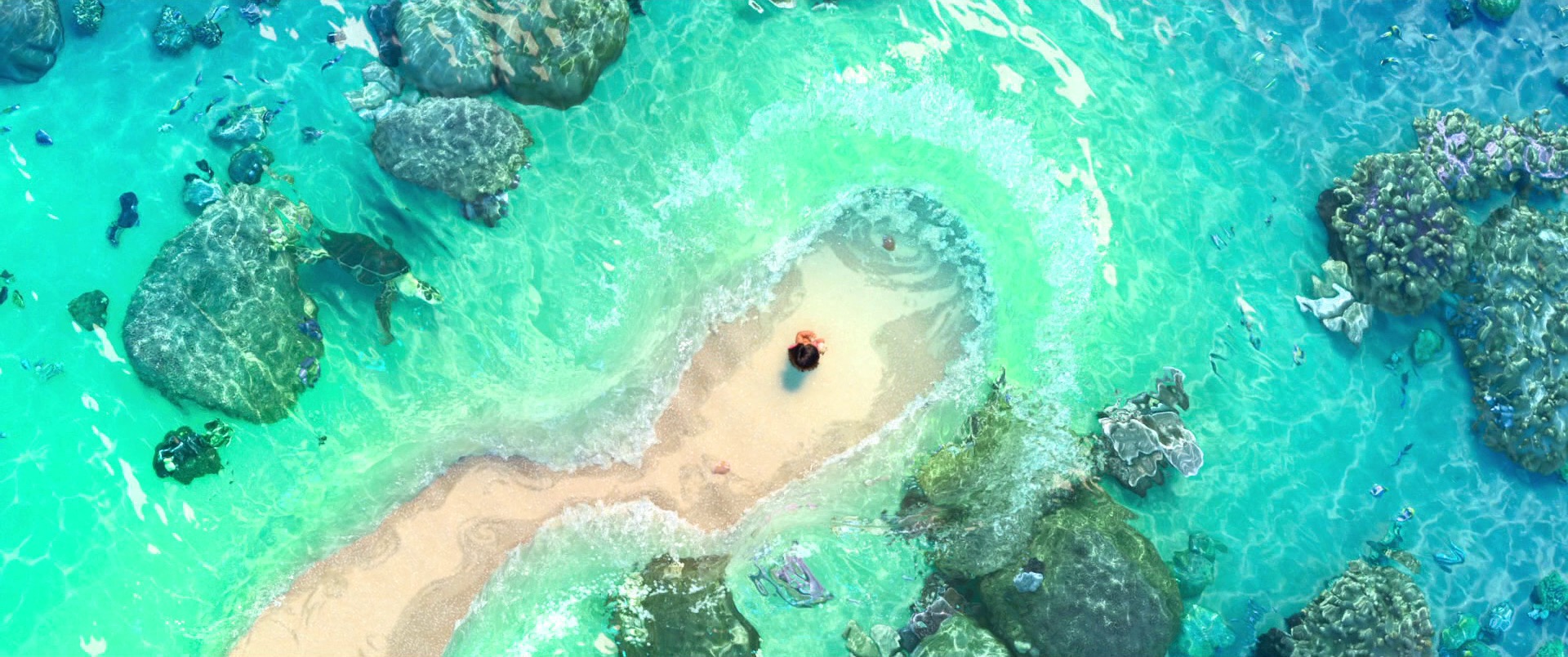

Hyperion gained a number of major new capabilities in support of making Moana. Rendering the ocean was a major concern on Moana, so much of Hyperion’s development during Moana revolved around features related to rendering water. Our lighters wanted caustics in all shots with shallow water, such as shots set at the beach or near the shoreline; faking caustics was quickly ruled out as an option since setting up lighting rigs with fake caustics that looked plausible and visually pleasing proved to be difficult and laborious. We found that providing real caustics was vastly preferable to faking things, both from a visual quality standpoint and a artist workflow standpoint, so we wound up adding a photon mapping system to Hyperion. The design of the photon mapping system is highly optimized around handling sun-water caustics, which allows for some major performance optimizations, such as an adaptive photon distribution system that makes sure that photons are not wasted on off-camera parts of the scene. Most of the photon mapping system was written by Peter Kutz; I also got to work on the photon mapping system a bit.

Water is in almost every shot in the film in some form, and the number of water effects was extremely varied, ranging from the ocean surface going out for dozens of miles in every direction, to splashes and boat wakes [Stomakhin and Selle 2017] and other finely detailed effects. Water had to be created using a host of different techniques, from relatively simple procedural wave functions [Garcia et al. 2016], to hand-animatable rigged wave systems [Byun and Stomakhin 2017], all the way to huge complex fluid simulations using Splash, a custom in-house APIC-based fluid simulator [Jiang et al. 2015]. We even had to support water as a straight up rigged character [Frost et al. 2017]! In order to bring the results of all of these techniques together into a single renderable water surface, an enormous amount of effort was put into building a level-set compositing system, in which all water simulation results would be converted into signed distance fields that could then be combined and converted into a watertight mesh. Having a single watertight mesh was important, since the ocean often also contained a homogeneous volume to produce physically correct scattering. This is where all of the blues and the greens in ocean water come from. This entire system could be run by Hyperion at rendertime, or could be run offline beforehand to generate a cached result that Hyperion could load; a whole complex pipeline had to be build to support this capability [Palmer et al. 2017]. Building this level-set compositing and meshing system involved a large number of TDs and engineers; on the Hyperion side, this project was led by Ralf Habel, Patrick Kelly, and Andy Selle. Peter and I also helped out at various points.

At one point early on the film’s production, we noticed that our lighters were having a difficult time getting specular glints off of the ocean surface to look right. For artistic controllability reasons, our lighters prefer to keep the sun and the skydome as two separate lights; the skydome is usually an image-based light that is either painted or is from photography with the sun painted out, and the sun is usually a distant infinite light that subtends some sold angle. After a lot of testing, we found that the look of specular glints on the ocean surface comes partially from the sun itself, but also partially from the atmospheric scattering that makes the sun look hazy and larger in the sky than it actually is. To get this look, I added a system to analytically add a Mie-scattering halo around our distant lights; we called the result the “halo light”.

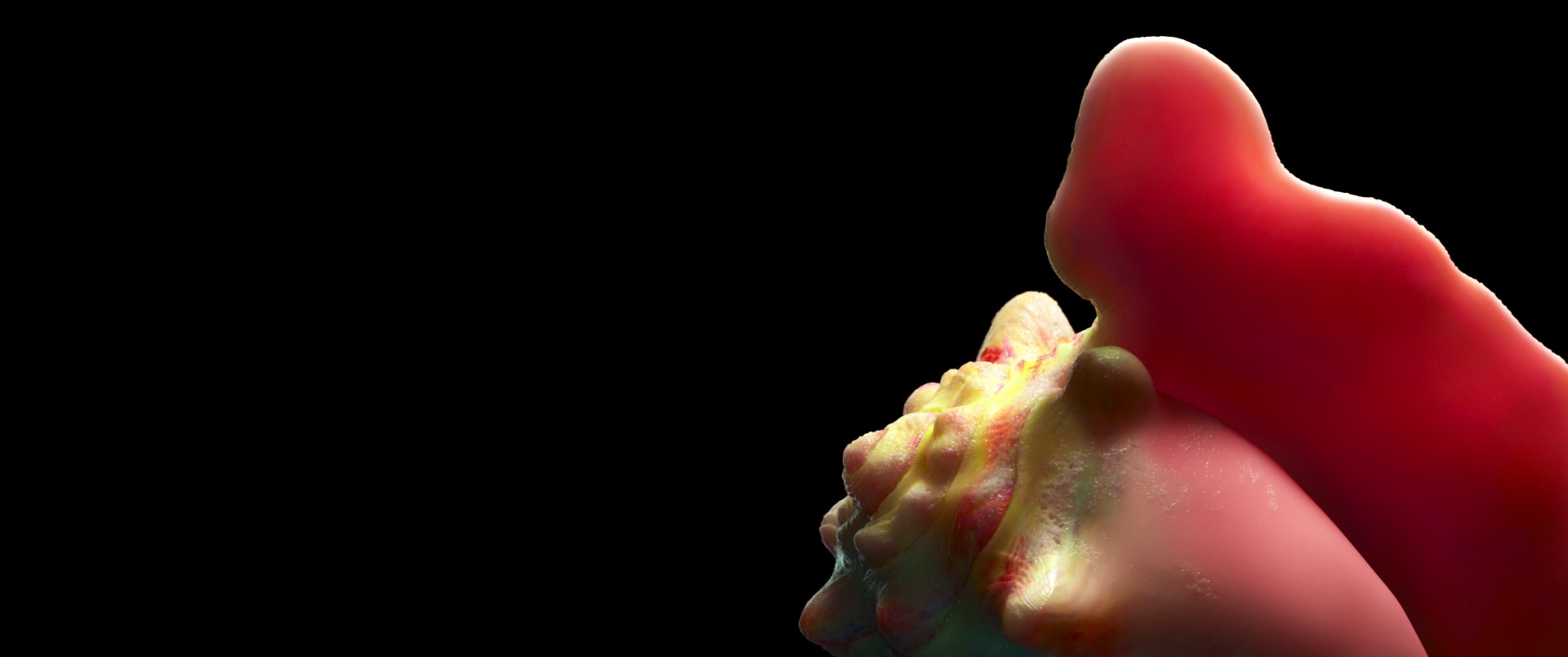

Up until Moana, Hyperion actually never had proper importance sampling for emissive meshes; we just relied on paths randomly finding their way to emissive meshes and only worried about importance sampling analytical area lights and distant infinite lights. For shots with the big lava monster Te-Ka [Bryant et al. 2017], however, most of the light in the frame came from emissive lava meshes, and most of what was being lit were complex, dense smoke volumes. Peter added a highly efficient system for importance sampling emissive meshes into the renderer, which made Te-Ka shots go from basically un-renderable to not a problem at all. David Adler also made some huge improvements to our denoiser’s ability to handle volumes to help with those shots.

Hyperion also saw a huge number of other improvements during Moana; Dan Teece and Matt Chiang made numerous improvements to the shading system, I reworked the ribbon curve intersection system to robustly handle Heihei’s and hawk-Maui’s feathers, Greg Nichols made our camera-adaptive tessellation more robust, and the team in general made many speed and memory optimizations. Throughout the whole production cycle, Hyperion partnered really closely with production to make Moana the most beautiful animated film we’ve ever made. This close partnership is what makes working at Disney Animation such an amazing, fun, and interesting experience.

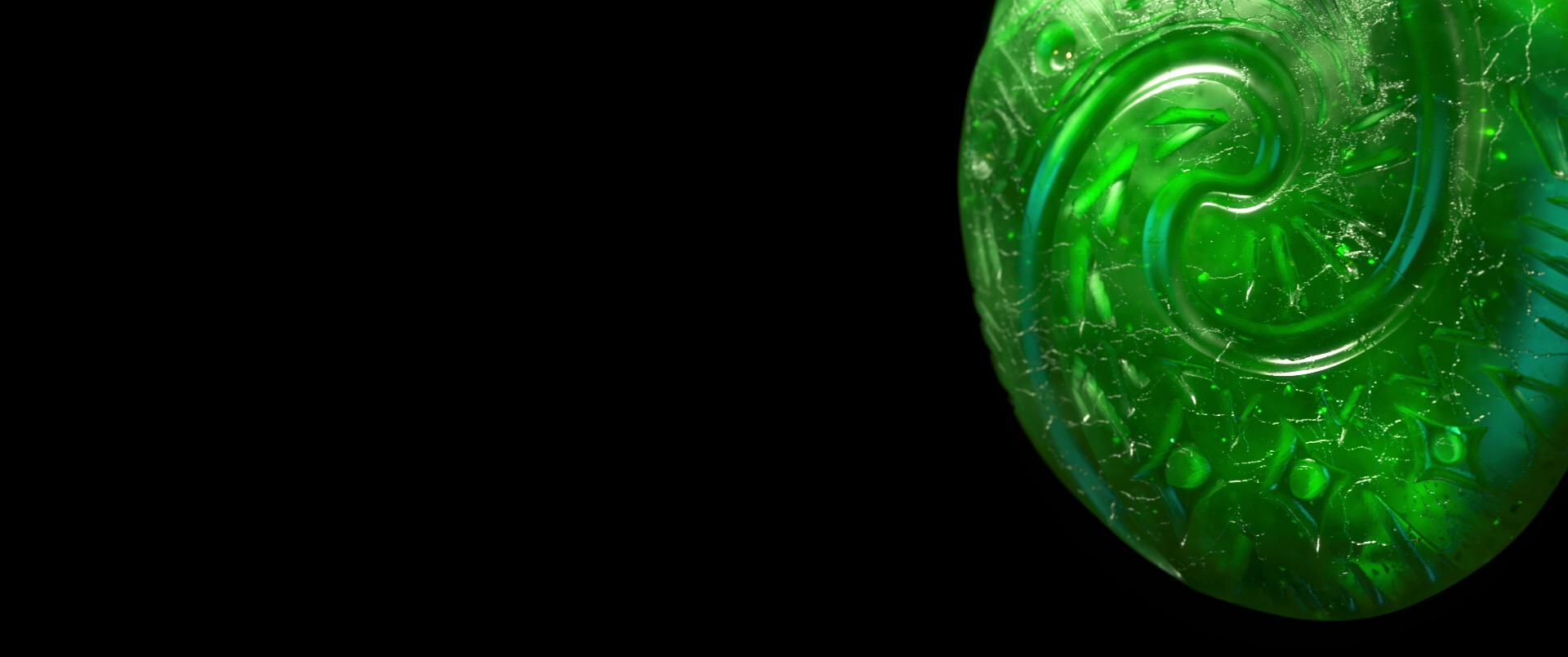

The first section of the credits sequence in Moana showcases a number of the props that our artists made for the film. I highly recommend staying and staring at all of the eye candy; our look and modeling departments are filled with some of the most dedicated and talented folks I’ve ever met. The props in the credits have simply preposterous amounts of detail on them; every single prop has stuff like tiny little flyaway fibers or microscratches or imperfections or whatnot on them. In some of the international posters, one can see that all of the human characters are covered with fine peach fuzz (an important part of making their skin catch the sunlight correctly), which we rendered in every frame! Something that we’re really proud of is the fact that none of the credit props were specially modeled for the credits! Those are all the exact props we used in every frame that they show up in, which really is a testament to both how amazing our artists our and how much work we’ve put into every part of our technology. The vast majority of production for Moana happened in essentially the 9 months between Zootopia’s release in March and October; this timeline becomes even more astonishing given the sheer beauty and craftsmanship in Moana.

Below are a number of stills (in no particular order) from the movie, 100% rendered using Hyperion. These stills give just a hint at how beautiful this movie looks; definitely go see it on the biggest screen you can find!

Here is a credits frame with my name that Disney kindly provided! Most of the Hyperion team is grouped under the Rendering/Pipeline/Engineering Services (three separate teams under the same manager) category this time around, although a handful of Hyperion guys show up in an earlier part of the credits instead.

All images in this post are courtesy of and the property of Walt Disney Animation Studios.

Addendum 2018-08-18

A lot more detailed information about the photon mapping system, the level-set compositing system, and the halo light is now available as part of our recent TOG paper on Hyperion [Burley et al. 2018].

References

Marc Bryant, Ian Coony, and Jonathan Garcia. 2017. Moana: Foundation of a Lava Monster. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2017 Talks. Article 10.

Brent Burley, David Adler, Matt Jen-Yuan Chiang, Hank Driskill, Ralf Habel, Patrick Kelly, Peter Kutz, Yining Karl Li, and Daniel Teece. 2018. The Design and Evolution of Disney’s Hyperion Renderer. ACM Transactions on Graphics 37, 3 (Jul. 2018), Article 33.

Dong Joo Byun and Alexey Stomakhin. 2017. Moana: Crashing Waves. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2017 Talks. Article 41.

Ben Frost, Alexey Stomakhin, and Hiroaki Narita. 2017. Moana: Performing Water. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2017 Talks. Article 30.

Jonathan Garcia, Sara Drakeley, Sean Palmer, Erin Ramos, David Hutchins, Ralf Habel, and Alexey Stomakhin. 2016. Rigging the Oceans of Disney’s Moana. In ACM SIGGRAPH Asia 2016 Technical Briefs. Article 30.

Chenfafu Jiang, Craig Schroeder, Andrew Selle, Joseph Teran, and Alexey Stomakhin. 2015. The Affine Particle-in-Cell Method. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH) 34, 4 (Aug. 2015), Article 51.

Sean Palmer, Jonathan Garcia, Sara Drakeley, Patrick Kelly, and Ralf Habel. 2017. The Ocean and Water Pipeline of Disney’s Moana. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2017 Talks. Article 29.

Alexey Stomakhin and Andy Selle. 2017. Fluxed Animated Boundary Method. ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. of SIGGRAPH) 36, 4 (Aug. 2017), Article 68.